TITLE: What is a Tree?

AUTHOR: Eugene Wallingford

DATE: January 30, 2008 8:39 AM

DESC:

-----

BODY:

I can talk about something other than science.

As I write this, I am at a talk called "What is a Tree?",

by computational artist

Ira Greenberg.

In it, Greenberg is telling his story of going from art

to math -- and computation -- and back.

Greenberg started as a traditional artist, based in drawing

and focused in painting. He earned his degrees in Visual

Art, from Cornell and Penn. His training was traditional,

too -- no computation, no math. He was going to paint.

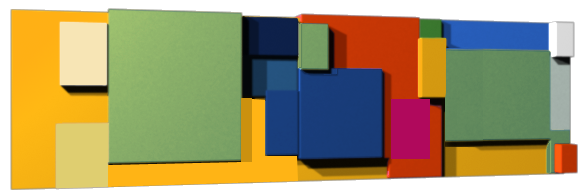

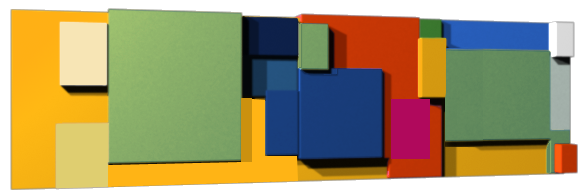

In his earliest work, Greenberg was caught up in perception.

He found that he could experiment only with the motif in

front of him. Over time he evolved from more realistic

natural images to images that were more "synthetic", more

plastic. His work came to be about shape and color. And

pattern.

I can talk about something other than science.

As I write this, I am at a talk called "What is a Tree?",

by computational artist

Ira Greenberg.

In it, Greenberg is telling his story of going from art

to math -- and computation -- and back.

Greenberg started as a traditional artist, based in drawing

and focused in painting. He earned his degrees in Visual

Art, from Cornell and Penn. His training was traditional,

too -- no computation, no math. He was going to paint.

In his earliest work, Greenberg was caught up in perception.

He found that he could experiment only with the motif in

front of him. Over time he evolved from more realistic

natural images to images that were more "synthetic", more

plastic. His work came to be about shape and color. And

pattern.

Alas, he wasn't selling anything. Like all of us, he needed

to make some money. His uncle told him to "look into

computers -- they are the future". (This is 1993 or so...)

Greenberg could not have been less interested. Working with

computers seemed like a waste of time. But he got a computer,

some software, and some books, and he played. In spite of

himself, he loved it. He was fascinated.

Soon he got paying gigs at places like Conde Nast. He was

making good money doing computer graphics for marketing and

publishing folks. At the time, he said, people doing

computer graphics were like mad scientists, conjuring

works with mystical incantations. He and his buddies found

work as a hired guns for older graphic artists who had no

computer skills. They would stand over his should, point

at the screen, and say in rapid-fire style, "Do this, do

this, do this." "We did, and then they paid us."

All the while, Greenberg was still doing his "serious work"

-- painting -- on side.

Alas, he wasn't selling anything. Like all of us, he needed

to make some money. His uncle told him to "look into

computers -- they are the future". (This is 1993 or so...)

Greenberg could not have been less interested. Working with

computers seemed like a waste of time. But he got a computer,

some software, and some books, and he played. In spite of

himself, he loved it. He was fascinated.

Soon he got paying gigs at places like Conde Nast. He was

making good money doing computer graphics for marketing and

publishing folks. At the time, he said, people doing

computer graphics were like mad scientists, conjuring

works with mystical incantations. He and his buddies found

work as a hired guns for older graphic artists who had no

computer skills. They would stand over his should, point

at the screen, and say in rapid-fire style, "Do this, do

this, do this." "We did, and then they paid us."

All the while, Greenberg was still doing his "serious work"

-- painting -- on side.

But he got good at this computer stuff. He liked it. And

yet he felt guilty. His artist friends were "pure", and

he felt like a sell-out. Even still, he felt an urge to

"put it all together", to understand what this computer

stuff really meant to his art. He decided to sell out all

the way: to go to NYC and sell these marketable skills for

big money. The time was right, and the money was good.

It didn't work. Going to an office to produce commercial

art for hire changed him, and his wife notice. Greenberg

sees nothing wrong with this kind of work; it just wasn't

for him. Still, he liked at least one thing about doing

art in the corporate style: collaboration. He was able

to work with designers, writers, marketing folks. Serious

painters don't collaborate, because they are doing their

own art.

The more he work with computers in the creative process,

the more he began to feel as if using tools like Photoshop

and LightWave was cheating. They provide an experience

that is too "mediated". With any activity, as you get

better you "let the chaos guide you", but these tools --

their smoothness, their engineered perfection, their Undo

buttons -- were too neat. Artists need fuzziness. He

wanted to get his hands dirty. Like painting.

So Greenberg decided to get under the hood of Photoshop.

He started going deeper. His artist friends thought he

was doing the devil's work. But he was doing cool stuff.

Oftentimes, he felt that the odd things generated by his

computer programs were more interesting than his painting!

But he got good at this computer stuff. He liked it. And

yet he felt guilty. His artist friends were "pure", and

he felt like a sell-out. Even still, he felt an urge to

"put it all together", to understand what this computer

stuff really meant to his art. He decided to sell out all

the way: to go to NYC and sell these marketable skills for

big money. The time was right, and the money was good.

It didn't work. Going to an office to produce commercial

art for hire changed him, and his wife notice. Greenberg

sees nothing wrong with this kind of work; it just wasn't

for him. Still, he liked at least one thing about doing

art in the corporate style: collaboration. He was able

to work with designers, writers, marketing folks. Serious

painters don't collaborate, because they are doing their

own art.

The more he work with computers in the creative process,

the more he began to feel as if using tools like Photoshop

and LightWave was cheating. They provide an experience

that is too "mediated". With any activity, as you get

better you "let the chaos guide you", but these tools --

their smoothness, their engineered perfection, their Undo

buttons -- were too neat. Artists need fuzziness. He

wanted to get his hands dirty. Like painting.

So Greenberg decided to get under the hood of Photoshop.

He started going deeper. His artist friends thought he

was doing the devil's work. But he was doing cool stuff.

Oftentimes, he felt that the odd things generated by his

computer programs were more interesting than his painting!

He went deeper with the mathematics, playing with formulas,

simulating physics. He began to

substitute formulas inside formulas

inside formulas. He -- his programs -- produced "sketches".

At some point, he came across

Processing,

"an open source programming language and environment for

people who want to program images, animation, and interactions".

This is a domain-specific language for artists, implemented

as an IDE for Java. It grew out of work done by John Maeda's

group at the MIT Media Lab. These days he programs in

ActionScript, Java, Flash, and Processing, and promotes

Processing as perhaps the best way for computer-wary artists

to get started computationally.

He went deeper with the mathematics, playing with formulas,

simulating physics. He began to

substitute formulas inside formulas

inside formulas. He -- his programs -- produced "sketches".

At some point, he came across

Processing,

"an open source programming language and environment for

people who want to program images, animation, and interactions".

This is a domain-specific language for artists, implemented

as an IDE for Java. It grew out of work done by John Maeda's

group at the MIT Media Lab. These days he programs in

ActionScript, Java, Flash, and Processing, and promotes

Processing as perhaps the best way for computer-wary artists

to get started computationally.

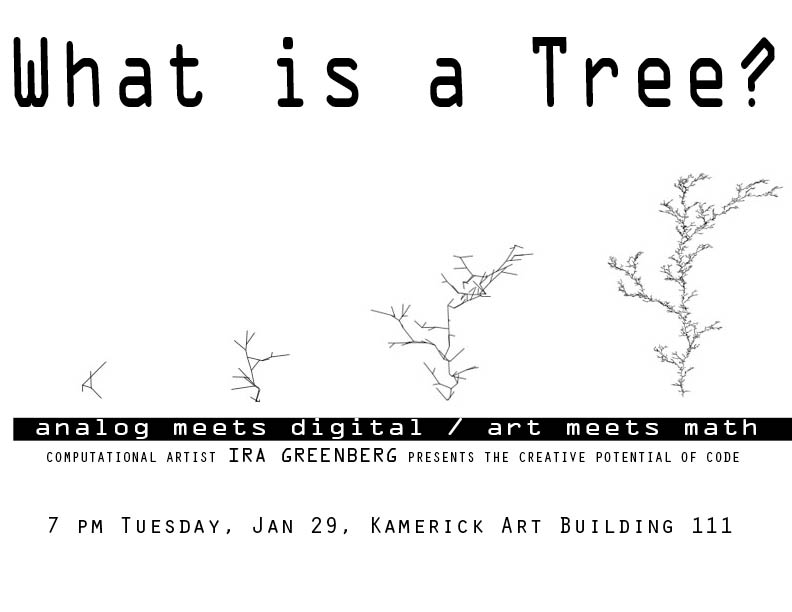

With his biographical sketch done, he moved on to the art

that inspired his talk's title. He showed a series of

programs that demonstrated his algorithmic approach to

creativity. His example was a tree, which was a double

entendré for his past as a painter of natural

scenes and also for his embrace of

computer science.

He started with the concept of a tree in a simple line

drawing. Then he added variation: different angles,

different branching factors. These created asymmetry

in the image. Then he added more variation: different

scales, different densities. Then he added more variation:

different line thickness, "foliage" at the end of the

smallest branches. With randomness elements in the

program, he gets different outputs each time he runs the

code. He added still more variation: color, space,

dimension, .... He can keep going along as many different

conceptual dimensions as he likes to create art. He can

strive for verisimilitude, representation, abstraction,

... any artistic goal he might seek with a brush and

oils.

Greenberg's artistic medium is code. He writes some code.

He runs it. He change some things, and runs it again.

This process is interactive with the medium. He evolves

not a specific work of art, but an algorithm that can generate

an infinite number of works.

I would claim that in a very important sense his work is

the algorithm. For most artists, the art is in the

physical work they produce. For Greenberg, there is a

level of indirection -- which is, interestingly, one of

the most fundamental concepts of computer science. For

me, perhaps the algorithm is the artistic work! Greenberg's

program is functional, not representational, and what

people want to see is the art his programs produce. But

code can be beautiful,

too.

-----

With his biographical sketch done, he moved on to the art

that inspired his talk's title. He showed a series of

programs that demonstrated his algorithmic approach to

creativity. His example was a tree, which was a double

entendré for his past as a painter of natural

scenes and also for his embrace of

computer science.

He started with the concept of a tree in a simple line

drawing. Then he added variation: different angles,

different branching factors. These created asymmetry

in the image. Then he added more variation: different

scales, different densities. Then he added more variation:

different line thickness, "foliage" at the end of the

smallest branches. With randomness elements in the

program, he gets different outputs each time he runs the

code. He added still more variation: color, space,

dimension, .... He can keep going along as many different

conceptual dimensions as he likes to create art. He can

strive for verisimilitude, representation, abstraction,

... any artistic goal he might seek with a brush and

oils.

Greenberg's artistic medium is code. He writes some code.

He runs it. He change some things, and runs it again.

This process is interactive with the medium. He evolves

not a specific work of art, but an algorithm that can generate

an infinite number of works.

I would claim that in a very important sense his work is

the algorithm. For most artists, the art is in the

physical work they produce. For Greenberg, there is a

level of indirection -- which is, interestingly, one of

the most fundamental concepts of computer science. For

me, perhaps the algorithm is the artistic work! Greenberg's

program is functional, not representational, and what

people want to see is the art his programs produce. But

code can be beautiful,

too.

-----

I can talk about something other than science.

As I write this, I am at a talk called "What is a Tree?",

by computational artist

Ira Greenberg.

In it, Greenberg is telling his story of going from art

to math -- and computation -- and back.

Greenberg started as a traditional artist, based in drawing

and focused in painting. He earned his degrees in Visual

Art, from Cornell and Penn. His training was traditional,

too -- no computation, no math. He was going to paint.

In his earliest work, Greenberg was caught up in perception.

He found that he could experiment only with the motif in

front of him. Over time he evolved from more realistic

natural images to images that were more "synthetic", more

plastic. His work came to be about shape and color. And

pattern.

I can talk about something other than science.

As I write this, I am at a talk called "What is a Tree?",

by computational artist

Ira Greenberg.

In it, Greenberg is telling his story of going from art

to math -- and computation -- and back.

Greenberg started as a traditional artist, based in drawing

and focused in painting. He earned his degrees in Visual

Art, from Cornell and Penn. His training was traditional,

too -- no computation, no math. He was going to paint.

In his earliest work, Greenberg was caught up in perception.

He found that he could experiment only with the motif in

front of him. Over time he evolved from more realistic

natural images to images that were more "synthetic", more

plastic. His work came to be about shape and color. And

pattern.

Alas, he wasn't selling anything. Like all of us, he needed

to make some money. His uncle told him to "look into

computers -- they are the future". (This is 1993 or so...)

Greenberg could not have been less interested. Working with

computers seemed like a waste of time. But he got a computer,

some software, and some books, and he played. In spite of

himself, he loved it. He was fascinated.

Soon he got paying gigs at places like Conde Nast. He was

making good money doing computer graphics for marketing and

publishing folks. At the time, he said, people doing

computer graphics were like mad scientists, conjuring

works with mystical incantations. He and his buddies found

work as a hired guns for older graphic artists who had no

computer skills. They would stand over his should, point

at the screen, and say in rapid-fire style, "Do this, do

this, do this." "We did, and then they paid us."

All the while, Greenberg was still doing his "serious work"

-- painting -- on side.

Alas, he wasn't selling anything. Like all of us, he needed

to make some money. His uncle told him to "look into

computers -- they are the future". (This is 1993 or so...)

Greenberg could not have been less interested. Working with

computers seemed like a waste of time. But he got a computer,

some software, and some books, and he played. In spite of

himself, he loved it. He was fascinated.

Soon he got paying gigs at places like Conde Nast. He was

making good money doing computer graphics for marketing and

publishing folks. At the time, he said, people doing

computer graphics were like mad scientists, conjuring

works with mystical incantations. He and his buddies found

work as a hired guns for older graphic artists who had no

computer skills. They would stand over his should, point

at the screen, and say in rapid-fire style, "Do this, do

this, do this." "We did, and then they paid us."

All the while, Greenberg was still doing his "serious work"

-- painting -- on side.

But he got good at this computer stuff. He liked it. And

yet he felt guilty. His artist friends were "pure", and

he felt like a sell-out. Even still, he felt an urge to

"put it all together", to understand what this computer

stuff really meant to his art. He decided to sell out all

the way: to go to NYC and sell these marketable skills for

big money. The time was right, and the money was good.

It didn't work. Going to an office to produce commercial

art for hire changed him, and his wife notice. Greenberg

sees nothing wrong with this kind of work; it just wasn't

for him. Still, he liked at least one thing about doing

art in the corporate style: collaboration. He was able

to work with designers, writers, marketing folks. Serious

painters don't collaborate, because they are doing their

own art.

The more he work with computers in the creative process,

the more he began to feel as if using tools like Photoshop

and LightWave was cheating. They provide an experience

that is too "mediated". With any activity, as you get

better you "let the chaos guide you", but these tools --

their smoothness, their engineered perfection, their Undo

buttons -- were too neat. Artists need fuzziness. He

wanted to get his hands dirty. Like painting.

So Greenberg decided to get under the hood of Photoshop.

He started going deeper. His artist friends thought he

was doing the devil's work. But he was doing cool stuff.

Oftentimes, he felt that the odd things generated by his

computer programs were more interesting than his painting!

But he got good at this computer stuff. He liked it. And

yet he felt guilty. His artist friends were "pure", and

he felt like a sell-out. Even still, he felt an urge to

"put it all together", to understand what this computer

stuff really meant to his art. He decided to sell out all

the way: to go to NYC and sell these marketable skills for

big money. The time was right, and the money was good.

It didn't work. Going to an office to produce commercial

art for hire changed him, and his wife notice. Greenberg

sees nothing wrong with this kind of work; it just wasn't

for him. Still, he liked at least one thing about doing

art in the corporate style: collaboration. He was able

to work with designers, writers, marketing folks. Serious

painters don't collaborate, because they are doing their

own art.

The more he work with computers in the creative process,

the more he began to feel as if using tools like Photoshop

and LightWave was cheating. They provide an experience

that is too "mediated". With any activity, as you get

better you "let the chaos guide you", but these tools --

their smoothness, their engineered perfection, their Undo

buttons -- were too neat. Artists need fuzziness. He

wanted to get his hands dirty. Like painting.

So Greenberg decided to get under the hood of Photoshop.

He started going deeper. His artist friends thought he

was doing the devil's work. But he was doing cool stuff.

Oftentimes, he felt that the odd things generated by his

computer programs were more interesting than his painting!

He went deeper with the mathematics, playing with formulas,

simulating physics. He began to

substitute formulas inside formulas

inside formulas. He -- his programs -- produced "sketches".

At some point, he came across

Processing,

"an open source programming language and environment for

people who want to program images, animation, and interactions".

This is a domain-specific language for artists, implemented

as an IDE for Java. It grew out of work done by John Maeda's

group at the MIT Media Lab. These days he programs in

ActionScript, Java, Flash, and Processing, and promotes

Processing as perhaps the best way for computer-wary artists

to get started computationally.

He went deeper with the mathematics, playing with formulas,

simulating physics. He began to

substitute formulas inside formulas

inside formulas. He -- his programs -- produced "sketches".

At some point, he came across

Processing,

"an open source programming language and environment for

people who want to program images, animation, and interactions".

This is a domain-specific language for artists, implemented

as an IDE for Java. It grew out of work done by John Maeda's

group at the MIT Media Lab. These days he programs in

ActionScript, Java, Flash, and Processing, and promotes

Processing as perhaps the best way for computer-wary artists

to get started computationally.

With his biographical sketch done, he moved on to the art

that inspired his talk's title. He showed a series of

programs that demonstrated his algorithmic approach to

creativity. His example was a tree, which was a double

entendré for his past as a painter of natural

scenes and also for his embrace of

computer science.

He started with the concept of a tree in a simple line

drawing. Then he added variation: different angles,

different branching factors. These created asymmetry

in the image. Then he added more variation: different

scales, different densities. Then he added more variation:

different line thickness, "foliage" at the end of the

smallest branches. With randomness elements in the

program, he gets different outputs each time he runs the

code. He added still more variation: color, space,

dimension, .... He can keep going along as many different

conceptual dimensions as he likes to create art. He can

strive for verisimilitude, representation, abstraction,

... any artistic goal he might seek with a brush and

oils.

Greenberg's artistic medium is code. He writes some code.

He runs it. He change some things, and runs it again.

This process is interactive with the medium. He evolves

not a specific work of art, but an algorithm that can generate

an infinite number of works.

I would claim that in a very important sense his work is

the algorithm. For most artists, the art is in the

physical work they produce. For Greenberg, there is a

level of indirection -- which is, interestingly, one of

the most fundamental concepts of computer science. For

me, perhaps the algorithm is the artistic work! Greenberg's

program is functional, not representational, and what

people want to see is the art his programs produce. But

code can be beautiful,

too.

-----

With his biographical sketch done, he moved on to the art

that inspired his talk's title. He showed a series of

programs that demonstrated his algorithmic approach to

creativity. His example was a tree, which was a double

entendré for his past as a painter of natural

scenes and also for his embrace of

computer science.

He started with the concept of a tree in a simple line

drawing. Then he added variation: different angles,

different branching factors. These created asymmetry

in the image. Then he added more variation: different

scales, different densities. Then he added more variation:

different line thickness, "foliage" at the end of the

smallest branches. With randomness elements in the

program, he gets different outputs each time he runs the

code. He added still more variation: color, space,

dimension, .... He can keep going along as many different

conceptual dimensions as he likes to create art. He can

strive for verisimilitude, representation, abstraction,

... any artistic goal he might seek with a brush and

oils.

Greenberg's artistic medium is code. He writes some code.

He runs it. He change some things, and runs it again.

This process is interactive with the medium. He evolves

not a specific work of art, but an algorithm that can generate

an infinite number of works.

I would claim that in a very important sense his work is

the algorithm. For most artists, the art is in the

physical work they produce. For Greenberg, there is a

level of indirection -- which is, interestingly, one of

the most fundamental concepts of computer science. For

me, perhaps the algorithm is the artistic work! Greenberg's

program is functional, not representational, and what

people want to see is the art his programs produce. But

code can be beautiful,

too.

-----