April 29, 2020 4:45 PM

Teaching Class is Like Groundhog Day

As I closed down my remote class session yesterday, I felt a familiar feeling... That session can be better! I've been using variations of this session, slowly improving it, for a few years now, and I always leave the classroom thinking, "Wait 'til next time." I'm eager to improve it now and iterate, trying it again tomorrow. Alas, tomorrow is another day, with another class session all its own. Next time is next year.

|

I feel this way about most of the sessions in most of my courses. Yesterday, it occurred to me that this must be what Phil Connors feels like in Groundhog Day.

Phil wakes up every day in the same place and time as yesterday. Part way through the film, he decides to start improving himself. Yet the next morning, there he is again, in the same place and time as yesterday, a little better but still flawed, in need of improvement.

Next spring, when I sit down to prep for this session, it will be like hitting that alarm clock and hearing Sonny and Cher all over again.

I told my wife about my revelation and my longing: If only I could teach this session 10,000 times, I'd finally get it right. You know what she said?

"Think how your students must feel. If they could do that session 10,000 times, they'd feel like they really got it, too."

My wife is wise. My students and I are in this together, getting a little better each day, we hope, but rarely feeling like we've figured all that much out. I'll keep plugging away, Phil Connors as CS prof. "Okay, campers, rise and shine..." Hopefully, today I'll be less wrong than yesterday. I wish my students the same.

Who knows, one of these days, maybe I'll leave a session and feel as Phil does in the last scene of the film, when he wakes up next to his colleague Rita. "Do you know what today is? Today is tomorrow. It happened. You're here." I'm not holding my breath, though.

April 19, 2020 4:10 PM

I Was a Library Kid, Too

Early in this Paris Review interview, Ray Bradbury says, "A conglomerate heap of trash, that's what I am." I smiled, because that's what I feel like sometimes, both culturally and academically. Later he confessed something that sealed my sense of kinship with him:

I am a librarian. I discovered me in the library. I went to find me in the library. Before I fell in love with libraries, I was just a six-year-old boy. The library fueled all of my curiosities, from dinosaurs to ancient Egypt.

|

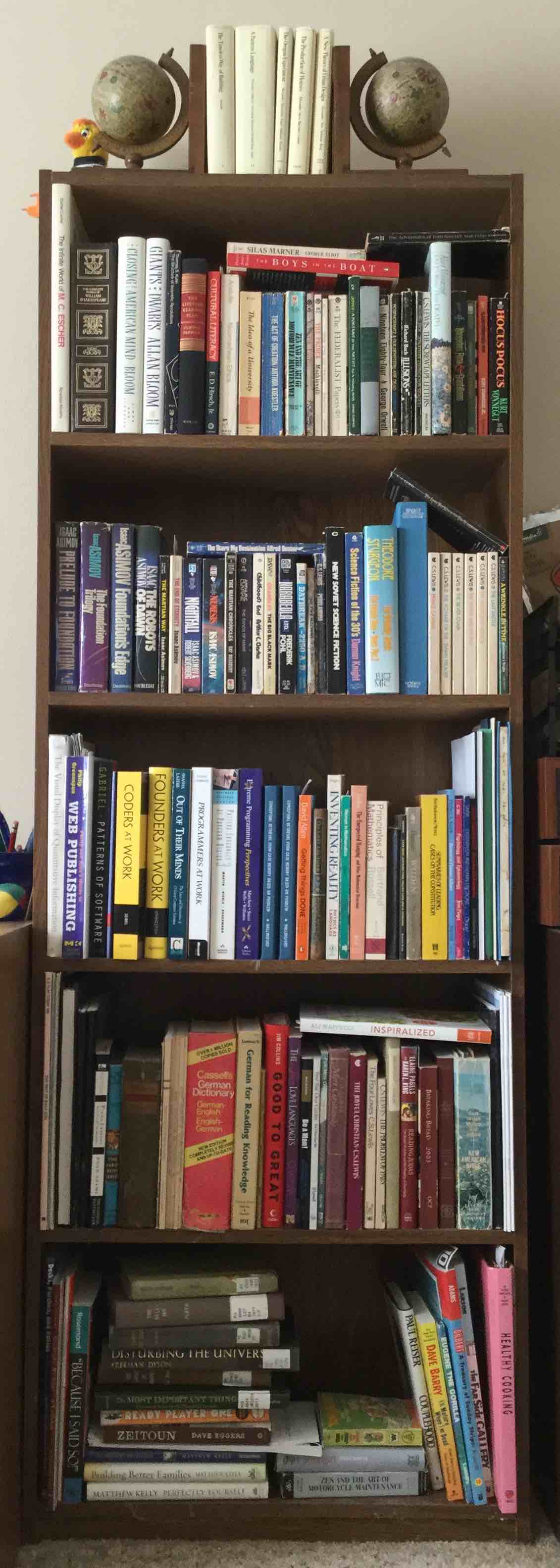

I was a library kid, too. I owned a few books, but I looked forward to every chance we had to go to the library. My grade school had books in every classroom, and my teachers shared their personal books with those of us who so clearly loved to read. Eventually my mom took me and my siblings to the Marion County public to get a library card, and the world of books available seemed limitless. When I got to high school, I spent free time before and after classes wandering the stacks, discovering science fiction, Vonnegut and Kafka and Voltaire, science and history. The school librarian got used to finding me in the aisles at times. She became as much a friend as any high school teacher could. So many of my friends have shelves and shelves of books; they talk about their addiction to Amazon and independent bookstores. But almost all of the books I have at home fit in a single bookshelf (at right). One of them is Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles, which I discovered in high school.

I do have a small chess library on another shelf across the room and a few sports books, most from childhood, piled nearby. I tried to get rid of the sports books once, in a fit of Marie Kondo-esque de-cluttering, but I just couldn't. Even I have an attachment to the books I own. Having so few, perhaps my attraction is even stronger than it might otherwise be, subject to some cosmic inverse square law of bibliophilia.

At my office, I do have two walls full of books, mostly textbooks accumulated over my years as a professor. When I retire, though, I'll keep only one bookcase full of those -- a few undergrad CS texts, yes, but mostly books I purchased because they meant something to me. Gödel, Escher, Bach. Metamagical Themas. Models of My Life. A few books about AI. These are books that helped me find me.

After high school, I was fortunate to spend a decade in college as an undergraduate and grad student. I would not trade those years for anything; I learned a lot, made friends with whom I remain close, and grew up. Bradbury, though, continued his life as an autodidact, going to the public library three nights a week for a decade, until he got married.

So I graduated from the library, when I was twenty-seven. I discovered that the library is the real school.

Even though I spent a decade as a student in college and now am a university prof, the library remains my second home. I rarely buy books to this day; I don't remember my last purchase. The university library is next to my office building, and I make frequent trips over in the afternoons. They give me a break from work and a chance to pick up my next read. I usually spend a lot more time there than necessary, wandering the stacks and exploring. I guess I'm still a library kid.

April 14, 2020 3:53 PM

Going Online, Three-Plus Weeks In

First the good news: after three more sessions, I am less despondent than I was after Week Two. I have taken my own advice from Week One and lowered expectations. After teaching for so many years and developing a decent sense of my strengths and weaknesses in the classroom, this move took me out of my usual groove. It was easy to forget in the rush of the moment not to expect perfection, and not being able to interact with students in the same way created different emotions about the class sessions. Now that I have my balance back, things feel a bit more normal.

Part of what changed things for me was watching the videos I made of our class sessions. I quickly realized that these sessions are no worse than my usual classes! It may be harder for students to pay attention to the video screen for seventy-five minutes in the same way they might pay attention in the classroom, but my actual presentation isn't all that different. That was comforting, even as I saw that the videos aren't perfect.

Another thing that comforted me: the problems with my Zoom sessions are largely the same as the problems with my classroom sessions. I can fall into the habit of talking too much and too long unless I carefully design exercises and opportunities for students to take charge. The reduced interaction channel magnifies this problem slightly, but it doesn't create any new problems in principle. This, too, was comforting.

For example, I notice that some in-class exercises work better than others. I've always know this from my in-person course sessions, but our limited interaction bandwidth really exposes problems that are at the wrong level for where the students are at the moment (for me, usually too difficult, though occasionally too easy). I am also remembering the value of the right hint at the right moment and the value of students interacting and sharing with one another. Improving on these elements of my remote course should result in corresponding improvements when we move back to campus.

I have noticed one new problem: I tend to lose track of time more easily when working with the class in Zoom, which leads me to run short on time at the end of the period. In the classroom, I glance at a big analog clock on the wall at the back of the room and use that to manage my time. My laptop has a digital clock in the corner, but it doesn't seem to help me as much. I think this is a function of two parameters: First, the clock on my computer is less obtrusive, so I don't look at it as often. Second, it is a digital clock. I feel the geometry of analog time viscerally in a way that I don't with digital time. Maybe I'm just old, or maybe we all experience analog clocks in a more physical way.

I do think that watching my lectures can help me improve my teaching. After Week One, I wondered, "In what ways can going online, even for only a month and a half, improve my course and materials?" How might this experience make me a better teacher or lead to better online materials? I have often heard advice that I should record my lectures so that I could watch them with an experienced colleague, with an eye to identifying strengths to build on and weaknesses to improve on. Even without a colleague to help, this few weeks of recording gives me a library of sessions I can use for self-diagnosis and improvement.

Maybe this experience will have a few positives to counterbalance its obvious negatives.

April 08, 2020 2:42 PM

Three Quotes on Human Behavior

2019, Robin Sloan:

On the internet, if you stop speaking: you disappear. And, by corollary: on the internet, you only notice the people who are speaking nonstop.

Some of the people speaking nonstop are the ones I wish would disappear for a while.

~~~~~

1947, from Italy's Response to the Coronavirus:

Published in 1947, The Plague has often been read as an allegory, a book that is really about the occupation of France, say, or the human condition. But it's also a very good book about plagues, and about how people react to them -- a whole category of human behavior that we have forgotten.

A good book is good on multiple levels.

~~~~~

1628, William Harvey, "On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals":

Doctrine, once sown, strikes deep its root, and respect for antiquity influences all men. Still the die is cast, and my trust is in my love of the truth and the candour of cultivated minds.

I don't know why, but the phrase "the candor of cultivated minds" really stuck with me when I read it this week.

April 06, 2020 1:57 PM

Arithmetic is Fundamental

From a September 2009 edition of Scientific American, in a research report titled "Animals by the Numbers":

Recent studies, however, have uncovered new instances of a counting skill in different species, suggesting that mathematical abilities could be more fundamental in biology than previously thought. Under certain conditions, monkeys could sometimes outperform college students.

Having watched college students attempt to convert base 10 to base 2 using a standard algorithm, I am not surprised.

One animal recorded with Kool-Aid, was 10 to 20 percent less accurate than college students but beat them in reaction time. "The monkeys didn't mind missing every once in a while," Cantlon recounts. "It wants to get past the mistake and on to the next problem where to can get more Kool-Aid, whereas college students can't shake their worry over guessing wrong."

Well, that's changes things a bit. Our education system trains a willingness to fail out of our students. Animals face different kinds of social pressure.

That said, 10-20 percent less accurate is only a letter grade or two on many grading scales. Not too bad for our monkey friends, and they get some Kool-Aid to boot.

My wife was helping someone clean out their house and brought home a bunch of old Scientific Americans. I've had a good time browsing through the articles and seeing what people were thinking and saying a decade ago. The September 2009 issue was about the origins of ideas and products, including the mind. Fun reading.

April 04, 2020 11:37 AM

Is the Magic Gone?

This passage from Remembering the LAN recalls an earlier time that feels familiar:

My father, a general practitioner, used this infrastructure of cheap 286s, 386s, and 486s (with three expensive laser printers) to write the medical record software for the business. It was used by a dozen doctors, a nurse, and receptionist. ...

The business story is even more astonishing. Here is a non-programming professional, who was able to build the software to run their small business in between shifts at their day job using skills learned from a book.

I wonder how many hobbyist programmers and side-hustle programmers of this sort there are today. Does programming attract people the way it did in the '70s or '80s? Life is so much easier than typing programs out of Byte or designing your own BASIC interpreter from scratch. So many great projects out on Github and the rest of the web to clone, mimic, adapt. I occasionally hear a student talking about their own projects in this way, but it's rare.

As Crawshaw points out toward the end of his post, the world in which we program now is much more complex. It takes a lot more gumption to get started with projects that feel modern:

So much of programming today is busywork, or playing defense against a raging internet. You can do so much more, but the activation energy required to start writing fun collaborative software is so much higher you end up using some half-baked SaaS instead.

I am not a great example of this phenomenon -- Crawshaw and his dad did much more -- but even today I like to roll my own, just for me. I use a simple accounting system I've been slowly evolving for a decade, and I've cobbled together bits and pieces of my own tax software, not an integrated system, just what I need to scratch an itch each year. Then there are all the short programs and scripts I write for work to make Spreadsheet City more habitable. But I have multiple CS degrees and a lot of years of experience. I'm not a doctor who decides to implement what his or her office needs.

I suspect there are more people today like Crawshaw's father than I hear about. I wish it were more of a culture that we cultivated for everyone. Not everyone wants to bake their own bread, but people who get the itch ought to feel like the world is theirs to explore.

April 03, 2020 2:05 PM

Going Online, Two Weeks In

Earlier in the week I read this article by Jason Fried and circled these sentences:

Ultimately this major upheaval is an opportunity. This is a chance for your company, your teams, and individuals to learn a new skill. Working remotely is a skill.

After two weeks of the great COVID-19 school-from-home adventure, I very much believe that teaching remotely is a skill -- one I do not yet have.

Last week I shared a few thoughts about my first week teaching online. I've stopped thinking of this as "teaching online", though, because my course was not designed as an online course. It was pushed online, like so many courses everywhere, in a state of emergency. The result is a course that has been optimized over many years for face-to-face synchronous interaction being taken by students mostly asynchronously, without much face-to-face interaction.

My primary emotion after my second week teaching remotely is disappointment. Switching to this new mode of instruction was simple but not easy, at least not easy to do well. It was simple because I already have so much textual material available online, including detailed lecture notes. For students who can read the class notes, do exercises and homework problems, ask a few questions, and learn on their own, things seem to be going fine so far. (I'll know more as more work comes in for evaluation.) But approximately half of my students need more, and I have not figured out yet how best to serve them well.

I've now hosted four class sessions via Zoom for students who were available at class time and interested or motivated enough to show up. With the exception of one student, they all keep their video turned off, which offers me little or no visual feedback. Everyone keeps their audio turned off except when speaking, which is great for reducing the distraction of noises from everybody's homes and keyboards. The result, though, is an eerie silence that leaves me feeling as if I'm talking to myself in a big empty room. As I told my students on Thursday, it's a bit unnerving.

With so little perceptual stimulus, time seems to pass quickly, at least for me. It's easy to talk for far too long. I'm spared a bit by the fact that my classes intersperse short exposition by me with interactive work: I set them a problem, they work for a while, and then we debrief. This sort of session, though, requires the students to be engaged and up to date with their reading and homework. That's hard for me to expect of them under the best of conditions, let alone now when they are dispersed and learning to cope with new distractions.

After a few hours of trying to present material online, I very much believe that this activity requires skill and experience, of which I have little of either at this point. I have a lot of work to do. I hope to make Fried proud and use this as an opportunity to learn new skills.

I had expected by this point to have created more short videos that I could use to augment my lecture notes, for students who have no choice but to work on the course whenever they are free. Time has been in short supply, though, with everything on campus changing all at once. Perhaps if I can make a few more videos and flip the course a bit more, I will both serve those students better and find a path toward using our old class time better for the students who show up then and deserve a positive learning experience.

At level of nuts and bolts, I have already begun to learn some of the details of Panopto, Zoom, and our e-learning system. I like learning new tools, though the complications of learning them all at once and trying to use them at the same time makes me feel like a tech newbie. I guess that never changes.

The good news is that other parts of the remote work experience are going better, sometimes even well. Many administrative meetings work fine on Zoom, because they are mostly about people sharing information and reporting out. Most don't really need to be meetings anyway, and participating via Zoom is an improvement over gathering in a big room. As one administrator said at the end of one meeting recently, "This was the first council meeting online and maybe the shortest council meeting ever." I call that a success.