TITLE: The Dawn of a New Age

AUTHOR: Eugene Wallingford

DATE: February 18, 2011 4:51 PM

DESC:

-----

BODY:

My world this week has been agog with the Watson match

on Jeopardy!. The victory by a computer over the

game's two greatest champions may well signal a new

era, in much the same way as the rise of the web and

the advent of search. I'd like to collect my thoughts

before writing anything detailed about the match

itself.

In anticipation of match, last week my Intelligent

Systems students and I began to talk about some of the

techniques that were likely being used by Watson under

the hood. When I realized how little they had learned

in their AI course about reasoning in the face of

uncertainty, I dusted off an old lecture from my AI

course, circa 2001. With a few tweaks and additions,

it held up well. Among its topics were probability and

Bayes' Law. In many ways, this material is more timely

today than it was then.

Early in the week, as I began to think about what this

match would mean for computing and for the world, I was

reminded by Peter Norvig's

The Machine Age

that, in so many ways, the Jeopardy! extravaganza

heralds a change already in progress. If you haven't

read it yet, you should.

The shift from classical AI to the data-driven AI that

underlies the advances Norvig lists happened while I

was in graduate school. I saw glimpses of it at

conferences on expert systems in finance and

accounting, where the idea of mining reams of data

seemed to promise new avenues for decision makers in

business. The data might be audited financial

statements of public corporations or, more tantalizing,

collected from grocery store scanners. But I was

embedded pretty deeply in a particular way of thinking

about AI, and I missed the paradigm shift.

What is most ironic for me is that my own work, which

involved writing programs that could construct legal

arguments using both functional knowledge of a domain

and case law, was most limited by the problem that we

see addressed in systems like Google and Watson: the

ability to work with the staggering volume of text that

makes up our case law. Today's statistical techniques

for processing language make extending my work and

seeing how well it works in large domains possible in

a way I could only dream of. And I never even

dreamed of doing it myself,

such was my interest in classical AI. (I

just needed a programmer,

right?)

There is no question that data-driven, statistical AI

has proven to be our most successful way to build

intelligent systems, particularly those of a certain

scale. As an engineering approach, it has won. It

may well turn out to be the best scientific approach

to understanding intelligence as well, but... For an

old classicist like me, there is something missing.

Google is more idiot savant than bon

vivant; more Rain Man than Man on the Street.

There was a telling scene in one of the many short

documentary films about Watson in which the lead

scientist on the project said something like, "People

ask me if I know why Watson gave the answer it did.

I don't how it got the answer right. I don't know how

it got the answer wrong." His point was that Watson

is so complex and so data-rich it can surprise us with

its answers. This is true, of course, and an important

revelation to many people who think that, because a

computer can only do what we program it to do, it can

never surprise or create.

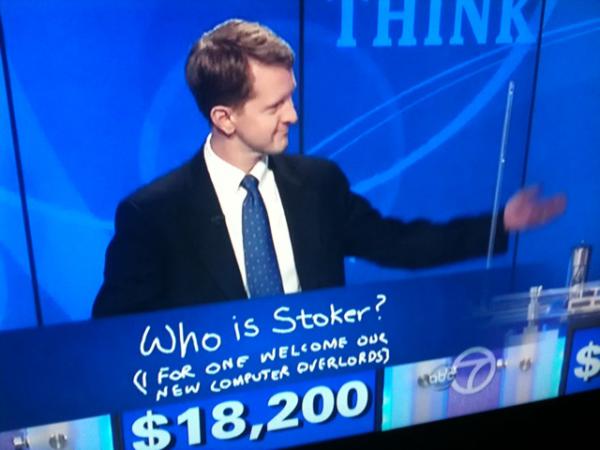

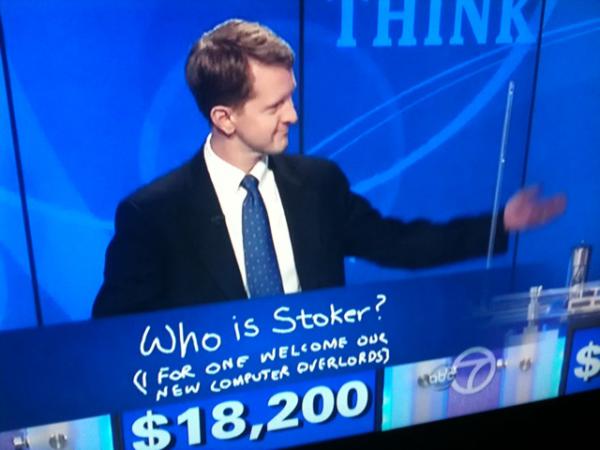

But immediately I was thinking about another sense of

that response. When Watson asks "What is Toronto? in

a Final Jeopardy! on "U.S. Cities", I want to ask it,

"What in the world were you thinking?" If it were a

human player, it might be able to tell about its

reasoning process. I'd be able to learn from what it

did right or wrong. But if I ask most computer programs

based on statistical computations over large data sets

"Why?" I can't get much more than the ranked lists of

candidates we saw at the bottom of the screen on

Jeopardy!

There is still a romantic part of me that wants to

understand what it means to think and reason at a

conscious level. Perhaps my introspection misleads me

with explanations constructed post hoc, but it

sure seems like I am able to think at a level above my

neurons firing. That feeling is especially strong when

I perform more complex tasks, such as writing a program

or struggling to understand a new idea.

So, when it comes to the science of AI, I still hope

for more. Maybe our statistical systems will become

complex and data-rich enough that they will be able

to explain their reasoning in a meaningful way. It's

also possible that my desire is nothing more than a

form of chauvinism for my own species, that the desire

to sit around and talk about stuff, including how and

why we think the way we do, is a quaint feature peculiar

to humans. I don't know the answer to this question,

but I can't shake the deep belief in an architecture

of thought and intelligent behavior that accounts for

metacognition.

In any case, it was fun to watch Watson put on such an

impressive show!

~~~~

If you are interested in such things, you might want to

(re-)read Newell and Simon's 1975 Turing Award lecture,

Computer Science as Empirical Inquiry: Symbols and Search.

It's a classic of the golden era of AI.

-----

My world this week has been agog with the Watson match

on Jeopardy!. The victory by a computer over the

game's two greatest champions may well signal a new

era, in much the same way as the rise of the web and

the advent of search. I'd like to collect my thoughts

before writing anything detailed about the match

itself.

In anticipation of match, last week my Intelligent

Systems students and I began to talk about some of the

techniques that were likely being used by Watson under

the hood. When I realized how little they had learned

in their AI course about reasoning in the face of

uncertainty, I dusted off an old lecture from my AI

course, circa 2001. With a few tweaks and additions,

it held up well. Among its topics were probability and

Bayes' Law. In many ways, this material is more timely

today than it was then.

Early in the week, as I began to think about what this

match would mean for computing and for the world, I was

reminded by Peter Norvig's

The Machine Age

that, in so many ways, the Jeopardy! extravaganza

heralds a change already in progress. If you haven't

read it yet, you should.

The shift from classical AI to the data-driven AI that

underlies the advances Norvig lists happened while I

was in graduate school. I saw glimpses of it at

conferences on expert systems in finance and

accounting, where the idea of mining reams of data

seemed to promise new avenues for decision makers in

business. The data might be audited financial

statements of public corporations or, more tantalizing,

collected from grocery store scanners. But I was

embedded pretty deeply in a particular way of thinking

about AI, and I missed the paradigm shift.

What is most ironic for me is that my own work, which

involved writing programs that could construct legal

arguments using both functional knowledge of a domain

and case law, was most limited by the problem that we

see addressed in systems like Google and Watson: the

ability to work with the staggering volume of text that

makes up our case law. Today's statistical techniques

for processing language make extending my work and

seeing how well it works in large domains possible in

a way I could only dream of. And I never even

dreamed of doing it myself,

such was my interest in classical AI. (I

just needed a programmer,

right?)

There is no question that data-driven, statistical AI

has proven to be our most successful way to build

intelligent systems, particularly those of a certain

scale. As an engineering approach, it has won. It

may well turn out to be the best scientific approach

to understanding intelligence as well, but... For an

old classicist like me, there is something missing.

Google is more idiot savant than bon

vivant; more Rain Man than Man on the Street.

There was a telling scene in one of the many short

documentary films about Watson in which the lead

scientist on the project said something like, "People

ask me if I know why Watson gave the answer it did.

I don't how it got the answer right. I don't know how

it got the answer wrong." His point was that Watson

is so complex and so data-rich it can surprise us with

its answers. This is true, of course, and an important

revelation to many people who think that, because a

computer can only do what we program it to do, it can

never surprise or create.

But immediately I was thinking about another sense of

that response. When Watson asks "What is Toronto? in

a Final Jeopardy! on "U.S. Cities", I want to ask it,

"What in the world were you thinking?" If it were a

human player, it might be able to tell about its

reasoning process. I'd be able to learn from what it

did right or wrong. But if I ask most computer programs

based on statistical computations over large data sets

"Why?" I can't get much more than the ranked lists of

candidates we saw at the bottom of the screen on

Jeopardy!

There is still a romantic part of me that wants to

understand what it means to think and reason at a

conscious level. Perhaps my introspection misleads me

with explanations constructed post hoc, but it

sure seems like I am able to think at a level above my

neurons firing. That feeling is especially strong when

I perform more complex tasks, such as writing a program

or struggling to understand a new idea.

So, when it comes to the science of AI, I still hope

for more. Maybe our statistical systems will become

complex and data-rich enough that they will be able

to explain their reasoning in a meaningful way. It's

also possible that my desire is nothing more than a

form of chauvinism for my own species, that the desire

to sit around and talk about stuff, including how and

why we think the way we do, is a quaint feature peculiar

to humans. I don't know the answer to this question,

but I can't shake the deep belief in an architecture

of thought and intelligent behavior that accounts for

metacognition.

In any case, it was fun to watch Watson put on such an

impressive show!

~~~~

If you are interested in such things, you might want to

(re-)read Newell and Simon's 1975 Turing Award lecture,

Computer Science as Empirical Inquiry: Symbols and Search.

It's a classic of the golden era of AI.

-----

My world this week has been agog with the Watson match

on Jeopardy!. The victory by a computer over the

game's two greatest champions may well signal a new

era, in much the same way as the rise of the web and

the advent of search. I'd like to collect my thoughts

before writing anything detailed about the match

itself.

In anticipation of match, last week my Intelligent

Systems students and I began to talk about some of the

techniques that were likely being used by Watson under

the hood. When I realized how little they had learned

in their AI course about reasoning in the face of

uncertainty, I dusted off an old lecture from my AI

course, circa 2001. With a few tweaks and additions,

it held up well. Among its topics were probability and

Bayes' Law. In many ways, this material is more timely

today than it was then.

Early in the week, as I began to think about what this

match would mean for computing and for the world, I was

reminded by Peter Norvig's

The Machine Age

that, in so many ways, the Jeopardy! extravaganza

heralds a change already in progress. If you haven't

read it yet, you should.

The shift from classical AI to the data-driven AI that

underlies the advances Norvig lists happened while I

was in graduate school. I saw glimpses of it at

conferences on expert systems in finance and

accounting, where the idea of mining reams of data

seemed to promise new avenues for decision makers in

business. The data might be audited financial

statements of public corporations or, more tantalizing,

collected from grocery store scanners. But I was

embedded pretty deeply in a particular way of thinking

about AI, and I missed the paradigm shift.

What is most ironic for me is that my own work, which

involved writing programs that could construct legal

arguments using both functional knowledge of a domain

and case law, was most limited by the problem that we

see addressed in systems like Google and Watson: the

ability to work with the staggering volume of text that

makes up our case law. Today's statistical techniques

for processing language make extending my work and

seeing how well it works in large domains possible in

a way I could only dream of. And I never even

dreamed of doing it myself,

such was my interest in classical AI. (I

just needed a programmer,

right?)

There is no question that data-driven, statistical AI

has proven to be our most successful way to build

intelligent systems, particularly those of a certain

scale. As an engineering approach, it has won. It

may well turn out to be the best scientific approach

to understanding intelligence as well, but... For an

old classicist like me, there is something missing.

Google is more idiot savant than bon

vivant; more Rain Man than Man on the Street.

There was a telling scene in one of the many short

documentary films about Watson in which the lead

scientist on the project said something like, "People

ask me if I know why Watson gave the answer it did.

I don't how it got the answer right. I don't know how

it got the answer wrong." His point was that Watson

is so complex and so data-rich it can surprise us with

its answers. This is true, of course, and an important

revelation to many people who think that, because a

computer can only do what we program it to do, it can

never surprise or create.

But immediately I was thinking about another sense of

that response. When Watson asks "What is Toronto? in

a Final Jeopardy! on "U.S. Cities", I want to ask it,

"What in the world were you thinking?" If it were a

human player, it might be able to tell about its

reasoning process. I'd be able to learn from what it

did right or wrong. But if I ask most computer programs

based on statistical computations over large data sets

"Why?" I can't get much more than the ranked lists of

candidates we saw at the bottom of the screen on

Jeopardy!

There is still a romantic part of me that wants to

understand what it means to think and reason at a

conscious level. Perhaps my introspection misleads me

with explanations constructed post hoc, but it

sure seems like I am able to think at a level above my

neurons firing. That feeling is especially strong when

I perform more complex tasks, such as writing a program

or struggling to understand a new idea.

So, when it comes to the science of AI, I still hope

for more. Maybe our statistical systems will become

complex and data-rich enough that they will be able

to explain their reasoning in a meaningful way. It's

also possible that my desire is nothing more than a

form of chauvinism for my own species, that the desire

to sit around and talk about stuff, including how and

why we think the way we do, is a quaint feature peculiar

to humans. I don't know the answer to this question,

but I can't shake the deep belief in an architecture

of thought and intelligent behavior that accounts for

metacognition.

In any case, it was fun to watch Watson put on such an

impressive show!

~~~~

If you are interested in such things, you might want to

(re-)read Newell and Simon's 1975 Turing Award lecture,

Computer Science as Empirical Inquiry: Symbols and Search.

It's a classic of the golden era of AI.

-----

My world this week has been agog with the Watson match

on Jeopardy!. The victory by a computer over the

game's two greatest champions may well signal a new

era, in much the same way as the rise of the web and

the advent of search. I'd like to collect my thoughts

before writing anything detailed about the match

itself.

In anticipation of match, last week my Intelligent

Systems students and I began to talk about some of the

techniques that were likely being used by Watson under

the hood. When I realized how little they had learned

in their AI course about reasoning in the face of

uncertainty, I dusted off an old lecture from my AI

course, circa 2001. With a few tweaks and additions,

it held up well. Among its topics were probability and

Bayes' Law. In many ways, this material is more timely

today than it was then.

Early in the week, as I began to think about what this

match would mean for computing and for the world, I was

reminded by Peter Norvig's

The Machine Age

that, in so many ways, the Jeopardy! extravaganza

heralds a change already in progress. If you haven't

read it yet, you should.

The shift from classical AI to the data-driven AI that

underlies the advances Norvig lists happened while I

was in graduate school. I saw glimpses of it at

conferences on expert systems in finance and

accounting, where the idea of mining reams of data

seemed to promise new avenues for decision makers in

business. The data might be audited financial

statements of public corporations or, more tantalizing,

collected from grocery store scanners. But I was

embedded pretty deeply in a particular way of thinking

about AI, and I missed the paradigm shift.

What is most ironic for me is that my own work, which

involved writing programs that could construct legal

arguments using both functional knowledge of a domain

and case law, was most limited by the problem that we

see addressed in systems like Google and Watson: the

ability to work with the staggering volume of text that

makes up our case law. Today's statistical techniques

for processing language make extending my work and

seeing how well it works in large domains possible in

a way I could only dream of. And I never even

dreamed of doing it myself,

such was my interest in classical AI. (I

just needed a programmer,

right?)

There is no question that data-driven, statistical AI

has proven to be our most successful way to build

intelligent systems, particularly those of a certain

scale. As an engineering approach, it has won. It

may well turn out to be the best scientific approach

to understanding intelligence as well, but... For an

old classicist like me, there is something missing.

Google is more idiot savant than bon

vivant; more Rain Man than Man on the Street.

There was a telling scene in one of the many short

documentary films about Watson in which the lead

scientist on the project said something like, "People

ask me if I know why Watson gave the answer it did.

I don't how it got the answer right. I don't know how

it got the answer wrong." His point was that Watson

is so complex and so data-rich it can surprise us with

its answers. This is true, of course, and an important

revelation to many people who think that, because a

computer can only do what we program it to do, it can

never surprise or create.

But immediately I was thinking about another sense of

that response. When Watson asks "What is Toronto? in

a Final Jeopardy! on "U.S. Cities", I want to ask it,

"What in the world were you thinking?" If it were a

human player, it might be able to tell about its

reasoning process. I'd be able to learn from what it

did right or wrong. But if I ask most computer programs

based on statistical computations over large data sets

"Why?" I can't get much more than the ranked lists of

candidates we saw at the bottom of the screen on

Jeopardy!

There is still a romantic part of me that wants to

understand what it means to think and reason at a

conscious level. Perhaps my introspection misleads me

with explanations constructed post hoc, but it

sure seems like I am able to think at a level above my

neurons firing. That feeling is especially strong when

I perform more complex tasks, such as writing a program

or struggling to understand a new idea.

So, when it comes to the science of AI, I still hope

for more. Maybe our statistical systems will become

complex and data-rich enough that they will be able

to explain their reasoning in a meaningful way. It's

also possible that my desire is nothing more than a

form of chauvinism for my own species, that the desire

to sit around and talk about stuff, including how and

why we think the way we do, is a quaint feature peculiar

to humans. I don't know the answer to this question,

but I can't shake the deep belief in an architecture

of thought and intelligent behavior that accounts for

metacognition.

In any case, it was fun to watch Watson put on such an

impressive show!

~~~~

If you are interested in such things, you might want to

(re-)read Newell and Simon's 1975 Turing Award lecture,

Computer Science as Empirical Inquiry: Symbols and Search.

It's a classic of the golden era of AI.

-----