I make it a point never to believe anything just because it's widely known to be so. -- Bill James

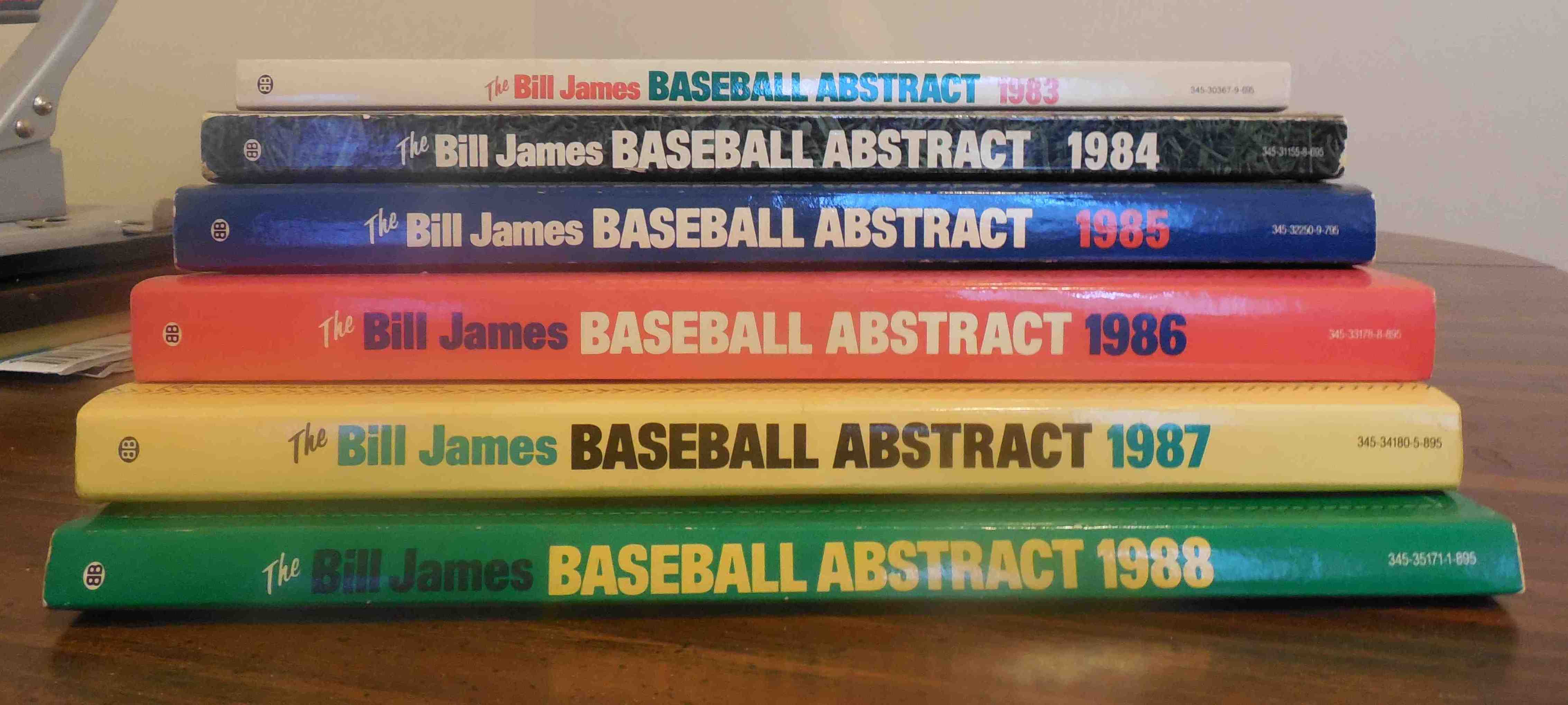

A few years ago, a friend was downsizing and sent me his collection of The Bill James Abstract from the 1980s. Every so often I'll pick one up and start reading. This week, I picked up the 1984 issue.

In many cases, I have no clear evidence on the issue, no way of answering the question. ... I guess what I'm saying is that if we start trying to answer these questions now, we'll be able to answer them in a few years. An unfortunate side effect is that I'm probably going to get some of the answers wrong now; not only some of the answers but some of the questions.Being wrong is par for the course for scientists; perhaps James felt some consolation in that this made him like Charles Darwin. The goal isn't to be right today. It is to be less wrong than yesterday. I love that James tells us that, early in his exploration, even some of the questions he is asking are likely the wrong questions. He will know better after he has collected some data. James applies his skepticism and meticulous analysis to everything in the game: which players contribute the most offense or defense to the team, and how; how pitching styles affect win probabilities; how managers approach the game. Some things are learned quickly but are rejected by the mainstream. By 1984, for example, James and people like him knew that, on average, sacrifice bunts and most attempts to steal a base reduced the number of runs a team scores, which means that most of them hurt the team more than they help. But many baseball people continued to use them too often tactically and even to build teams around them strategically. At the time of this issue, James had already developed models for several phenomena in the game, refined them as evidence from new seasons came in, and expanded his analysis into new areas. At each step, he channels his inner scientist: look at some part of the world, think about why it might work the way it does, develop a theory and a mathematical model, test the theory with further observations, and revise. James also loves to share his theories and results with the rest of us. There is nothing new here, of course. Sabermetrics is everywhere in baseball now, and data analytics have spread to most sports. By now, many people have seen Moneyball (a good movie) or read the Michael Lewis book on which it was based (even better). Even so, it really is cool to read what are in effect diaries recording what James is thinking as he learns how to apply the scientific method to baseball. His work helped move an entire industry into the modern world. The writing reflects the curiosity, careful thinking, and humility that so often lead to the goal of the scientific mind: