October 28, 2007 7:03 PM

This One Was 26.2 Miles, Too — Trust Me

First, I'll cut to the chase: 3:47:01.

I feel good about my result. The most meaningful measure of success for me is that I ran the race I planned: a careful first 20 miles, paying special attention to the uphill and downhill stretches, followed by a faster last 6 miles, with some strength. The only deviation from plan was that most of my miles were a bit slower than planned. I never really found my groove and saw mile splits that were all over the board. The hills early in the course had a lot to do with that, too.

But Miles 20-24 went very well, which allowed me to feel something I had not felt in at least three years: strong down the stretch. The last hill came at about 25.5, as we climbed from a highway down near the river up to the Marine Corps War Memorial. That made a fast finish impossible for me, but I ran hard and felt proud.

As a result, though, I did run my tank empty, and so the hour after the race was a little uneasy. But some rest on the metro, a shower, and several pieces of dandy pizza have refreshed me! My legs are still complaining, but that I can take.

This race had fewer novelty runners and humorous shirts and signs than my previous mega-race, in Chicago. My two favorite inspiration along the way were:

- In a wide open stretch between the halfway point and the 14-mile marker, a van was playing music and and advertising its wares. The side of the van read "3:16 — Your Race Number for Life!" I thought that was a creative twist on the usual "John 3:16" one sees at most sporting events.

- Somewhere around Mile 19, a spectator was holding a sign that featured a young woman eating an ice cream cone, um, suggestively. The sign read, "You Can Lick This Marathon". This made me smile as I entered my stretch run.

Of course, the inspiration in this race comes from the men and women of our armed forces. Many ran this race in honor of fallen comrades. Spouses ran in honor of active personnel in Iraq. Veterans ran, including some who had lost legs and so competed in the wheelchair division. Some ran with backpacks that made my load seem cheap. Many Marines did not run and instead served us, from the bag check before the race, through water stops along the course, to the recently-minted second lieutenants draping medals over our necks and honoring our effort. All I could say to them was "thank you" and think how much greater their efforts are every day, whether here or serving in harm's way. Oo-rah.

This was my second best time ever, just 77 seconds slower than Des Moines. But that was three years ago, and I have had much better preparation the last two years. I think this is another positive I can take from this year -- a good run in what was not the best health and training year I have had.

But I won't be running tomorrow.

October 27, 2007 5:31 PM

Another Reason to Support Education

(Update: I added a new closing paragraph, which got lost when editing the original post.)

... and especially, these days, in science and technology:

Human beings have had to guess about almost everything for the past million years or so. The leading characters in our history books have been our most enthralling, and sometimes our most terrifying, guessers. ...

And the masses of humanity through the ages, feeling inadequately educated just like we do now, and rightly so, have had little choice but to believe this guesser or that guesser.

-- Kurt Vonnegut, "A Man Without a Country"

And Vonnegut, humanist that he was, even had a university degree in chemistry. Today, everyone needs to understand science and technology to make sense of almost anything that happens in this world. But they also need to know history and political science and economics and finance, to understand the world. I also think that knowing a little about literature and the arts can help us make our way, in addition to making our lives more enjoyable.

Please forgive me if I continue to focus on the science and technology side of the equation. But keeping learning — and teaching others — whatever and wherever you can.

I do disagree with Vonnegut in at least one regard. He seems to think that, by relying on information, leaders can stop being guessers, that they can instead be deducers. But any substantial problem is too large to be solved purely by deduction, and the problems we face in the world are certainly more than just substantial. I think that informed guessing is the best we can do. Doing science and math prepares one to understand this, and to understand that even our informed guesses are always contingent. This is, of course, yet another reason to teach folks science and math.

October 24, 2007 4:12 PM

Missing OOPSLA

I am sad this week to be missing OOPSLA 2007. You might guess from my recent positive words that missing the conference would make me really sad, and you'd be right. But demands of work and family made traveling to Montreal a work infeasible. After attending eleven straight OOPSLAs, my fall schedule has a whole in it. My blog might, too; OOPSLA has been the source of many, many writing inspirations in the three years since I began blogging.

One piece of good news for me -- and for you, too -- is that we are podcasting all of OOPSLA's keynote talks this year. That would be a bonus for any conference, but with OOPSLA it is an almost sinfully delicious treat. I was reading someone else's blog recently, and the writer -- a functional programming guy, as I recall -- went down the roster of OOPSLA keynote speakers:

- Peter Turchi

- Kathy Sierra

- Jim Purbrick & Mark Lentczner

- Guy Steele & Richard Gabriel

- Fred Brooks

- John McCarthy

- David Parnas

- Gregor Kiczales

- Pattie Maes

... and wondered if this was perhaps the strongest lineup of speakers ever assembled for a CS conference. It is an impressive list!

If you are interested in listening in on what these deep thinkers and contributors to computing are telling the OOPSLA crowd this week, checkout the conference podcast page. We have all of Tuesday's keynotes (through Steele & Gabriel in the above list) available now, and we hope to post today's and tomorrow's audio in the next day or so. Enjoy!

October 24, 2007 11:24 AM

Gonna Fly Now

5:00 AM on a chilly autumn morning. A crystal clear sky filled with more stars than the eye can take in. A lone runner moves through the empty streets of a sleeping city, with only a hooded sweatshirt as protection against the intermittent gusts of wind.

As I completed my final training run this morning, my overly romantic subconscious felt like Rocky -- I half-expected to hear Bill Conti's theme rise over the trees of South Riverside Trail. Of course, Rocky ran against the backdrop of a blue-collar metropolis waking for another work day, among a people who placed great hope in one of their own to rise from the streets in victory. When I finished running, I headed off to my office for a day of mail, meetings, and a comfortable chair.

Rocky faced the challenge of Apollo Creed, who put on a cloak of transparent patriotism as America's hero. My challenge, the Marine Corps Marathon, offers a background of patriotism and pride, but an authentic pride borne of sacrifice my men and women who endure challenges that dwarf my 26.2 miles.

Rocky looked into the unknown as he prepared for a world championship fight, but this is my fourth marathon. I know the challenge. I have had some successes, and I've come up short of expectations. Each race is an unknown, but we understand some unknowns better than others.

I cannot in good conscience compare my cliché-riddled state of mind to Rocky's quiet desperation that his life could be more -- that he could be more. But on those mornings filled with long and solitary miles, we share something of a bond, along with countless others who challenge themselves to approach their limits. I, for one, enjoy it all -- the planning, the training miles, the race strategy, and lining up to see how far I can go.

October 19, 2007 4:42 PM

Working Hard, Losing Ground

Some days I read a paper or two and feel like I've lost ground. I just have more to read, think, and do. Of course, this phenomenon is universal... As Design Observer tells us, reading makes us more ignorant:

According to the Mexican critic Gabriel Zaid, writing in "So Many Books: Reading and Publishing in an Age of Abundance", ... "If a person read a book a day, he would be neglecting to read 4,000 others... and his ignorance would grow 4,000 times faster than his knowledge."

Don't read a book today! Now there is a slogan modern man can get behind. It seems that a few college students have already signed on.

My hope for most days is just the opposite. Here is a nice graphic slogan for this hope, courtesy of Brian Marick:

But it's hard to feel that way some days. The universe of knowing and doing is large. The best antidote to Sisyphean despair is to set a few measurable goals that one can reach with a reasonable short-term effort. Each step can give a bit of satisfaction, and -- if you take enough such steps -- you can end up someplace new. A lot like writing code.

October 18, 2007 8:40 AM

Project-Based Computer Science Education

[Update: I found the link to Michael Mitzenmacher's blog post on programming in theory courses and added it below.]

A couple of days ago, a student in my compilers course was in my office discussing his team's parser project. He was clearly engaged in the challenges that they had faced, and he explained a few of the design decisions they had made, some of which he was proud of and some of which he was less thrilled with. In the course of conversation, he said that he prefers project courses because he learns best when he gets into the trenches and builds a system. He contrasted this to his algorithms course, which he enjoyed but which left him with a nagging sense of incompleteness -- because they never wrote programs.

(One can, of course, ask students to program in an algorithms course. In my undergraduate algorithms, usually half of the homework involves programming. My recent favorite has been a Bloom filters project. Michael Mitzenmacher has written about programming in algorithms courses in his blog My Biased Coin.)

I have long been a fan of "big project" courses, and have taught several different ones, among them intelligent systems, agile software development, and recently compilers. So it was with great interest I read (finally) Philip Greenspun's notes on improving undergraduate computer science education. Greenspun has always espoused a pragmatic and irreverent view of university education, and this piece is no different. With an eye to the fact that a great many (most?) of our students get jobs as professional software developers, he sums up one of traditional CS education's biggest weaknesses in a single thought: We tend to give our students

a tiny piece of a big problem, not a small problem to solve by themselves.

This is one of the things that makes most courses on compilers -- one of the classic courses in the CS curriculum -- so wonderful. We usually give students a whole problem, albeit a small problem, not part of a big one. Whatever order we present the phases of the compiler, we present them all, and students build them all. And they build them as part of a single system, capable of compiling a complete language. We simplify the problem by choosing (or designing) a smallish source language, and sometimes by selecting a smallish target machine. But if we choose the right source and target languages, students must still grapple with ambiguity in the grammar. They must still grapple with design choices for which there is no clear answer. And they have to produce a system that satisfies a need.

Greenspun makes several claims with which I largely agree. One is this:

Engineers learn by doing progressively larger projects, not by doing what they're told in one-week homework assignments or doing small pieces of a big project.

Assigning lots of well-defined homework problems is a good way to graduate students who are really good at solving well-defined homework problems. The ones who can't learn this skill change majors -- even if they would make good software developers.

Here is another Greenspun claim. I think that it is likely even more controversial among CS faculty.

Everything that is part of a bachelor's in CS can be taught as part of a project that has all phases of the engineering cycle, e.g., teach physics and calculus by assigning students to build a flight simulator.

Many will disagree. I agree with Greenspun, but to act on this idea would, as Greenspun knows, require a massive change in how most university CS departments -- and faculty -- operate.

This idea of building all courses around projects is similar to an idea I have written about many times here, the value of teaching CS in the context of problems that matter, both to students and to the world. One could teach in the context of a problem domain that requires computing without designing either the course or the entire curriculum around a sequence of increasingly larger projects. But I think the two ideas have more in common than they differ, and problem-based instruction will probably benefit from considering projects as the centerpiece of its courses. I look forward to following the progress of Owen Astrachan's Problem Based Learning in Computer Science initiative to see what role projects will play in its results. Owen is a pragmatic guy, so I expect that some valuable pragmatic ideas will come out of it.

Finally, I think students and employers alike will agree with Greenspun's final conclusion:

A student who graduates with a portfolio of 10 systems, each of which he or she understands completely and can show off the documentation as well as the function (on the Web or on the student's laptop), is a student who will get a software development job.

Again, a curriculum that requires students to build such a portfolio will look quite different from most CS curricula these days. It will also require big changes in how CS faculty teach almost every topic.

Do read Greenspun's article. He is thought-provoking, as always. And read the comments; they contain some interesting claims, too, including the suggestion that we redesign CS education as professional graduate degree program along the lines of medicine.

Posted by Eugene Wallingford | Permalink | Categories: Computing, Software Development, Teaching and Learning

October 16, 2007 6:45 AM

Some Thoughts on How to Increase CS Enrollments

The latest issue of Communications of the ACM (Volume 50, Number 10, pages 67-71) contains an article by Asli Yagmur Akbulut and Clayton Arlen Looney called Inspiring Students to Pursue Computing Degrees. With that title, how could I not jump to it and read it immediately?

Most of the paper describes a survey of the sort that business professors love to do but which I find quite dull. Still, both the ideas that motivate the survey and the recommendations the authors make at the end are worth thinking about.

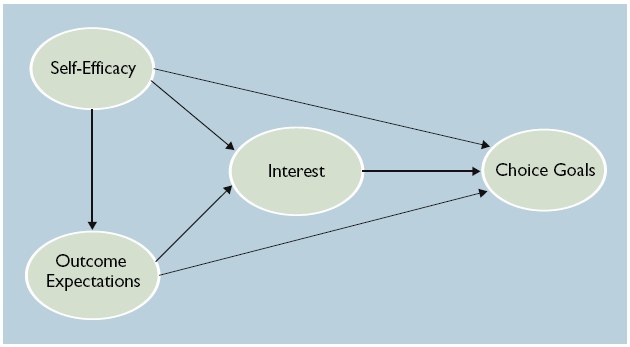

First, Akbulut and Looney base their research on a model derived from social cognitive theory called the Major Choice Goals Model. In this model, a person's choice goal (such as the choice to major in computing) is influenced by her interest in the area, the rewards she expects to receive as a result of the choice, and her belief that she can succeed in the area, which is termed self-efficacy. Interest itself is influenced by expected rewards and self-efficacy, and expected rewards are influenced by self-efficacy.

Their survey of business majors in an introductory business computing course found that choice goals were determined primarily by interest, and that the the other links in the model also correlated significantly. If their findings generalize, then...

- The key to increasing the number of computing majors lies in increasing their interest in the discipline.

- Talking to students about the financial and other rewards of majoring in computing influence their choice to major in the discipline only indirectly, through increased interest.

- Self-efficacy -- a student's judgment of her capability to perform effectively in the majors -- strongly affects both interest and outcome expectations.

I don't suppose that these results are all that earth-shaking, but they do give us clues on where we might best focus our efforts to recruit more majors.

First, we need to foster "a robust sense of self-efficacy" in potential students. This is most effective when we work with people who have little or no direct experience. We should strive to help these folks have successful, positive first experiences. When we encounter people who have had bad past experiences with computing, we need to work extra hard to overcome these with positive exposure.

Second, we need to enhance students' outcome expectations in a broader set of outcomes than just the lure of high salaries and plentiful jobs. Most of us have been looking for opportunities to share salary and employment data with students. But outcome expectations seem to affect a student's choice of majoring in computing mostly through increased interest in the discipline, and financial reward is only one, rather narrow, avenue to interest. We should communicate as many different kinds of rewards as possible, via as many different routes as possible, including different kinds of people who have reaped these benefits such as peer groups, alumni, and various IT professionals.

Third, we can seek to increase interest more directly. Again, this is something that most people in CS and IT have already been doing. I think the value Akbulut and Looney add here is in looking to the learning literature for influences on interest. These include the effective use of "novelty, complexity, conflict, and uncertainty". They remind us that "As technologies continue to rapidly evolve, it is important to deliver course content that is fresh, current, and aligned with students' interests". Our students are looking for ideas that they can apply to their own experiences and to open problems in the world.

The authors also make a suggestion that is controversial with many CS faculty but basic knowledge to others: In order to build self-efficacy and interest in students, we need to be sure that

... the most appropriate faculty are assigned to introductory computing courses. Instructors who are personable, fair, innovative, engaging, and can serve as role models would be more likely to attract larger pools of students.

This isn't pandering; it is simply how the world works. As someone who now has a role in assigning faculty to teach courses, I know that this can be a difficult task, both in making the choices and in working with faculty who would prefer different assignments.

When I first dug into the paper, I had some reservations. I'm not a big fan of this kind of research, because it seems too contingent on too many external factors to be convincing on its own. This particular study looked at business students and a very soft sort of computing course (Introduction to Information Systems) that all business students have to take at many universities. Do the findings apply to CS students more generally, or students who might be interested in a more technical sense of computing? In the end, though, this paper gave me a different spin on a couple of issues with which we have been grappling, in particular on students' sense that they can succeed in computing and on the indirect relationship between expected rewards and choice of major. This perspective gives me something useful to work with.

October 13, 2007 6:01 PM

More on Forth and a New Compilers Course

Remember this as a reader--whatever you are reading

is only a snapshot of an ongoing process of learning

on the part of the author.

-- Kent Beck

Sometimes, learning opportunities on a particular topic seem to come in bunches. I wrote recently about revisiting Forth and then this week ran across an article on Lambda the Ultimate called Minimal FORTH compiler and tutorial. The referenced compiler and tutorial are an unusually nice resource: a "literate code" file that teaches you as it builds. But then you also get the discussion that follows, which points out what makes Forth special, some implementation tricks, and links to several other implementations and articles that will likely keep me busy for a while.

Perhaps because I am teaching a compilers course right now, the idea that most grabbed my attention came in a discussion near the end of the thread (as of yesterday) on teaching language. Dave Herman wrote:

This also makes me think of how compilers are traditionally taught: lexing → parsing → type checking → intermediate language → register allocation → codegen. I've known some teachers to have success in going the other way around: start at the back end and move your way forward. This avoids giving the students the impression that software engineering involves building a product, waterfall-style, that you hope will actually do something at the very, *very* end -- and in my experience, most courses don't even get there by the end of the semester.

I have similar concerns. My students will be submitting their parsers on Monday, and we are just past the midpoint of our semester. Fortunately, type checking won't take long, and we'll be on to the run-time system and target code soon. I think students do feel satisfaction at having accomplished something along the way at the end of the early phases. The parser even give two points of satisfaction: when it can recognize a legal program (and reject an illegal on), and then when it produces an abstract syntax tree for a legal program. But those aren't the feeling of having compiled a program from end to end.

The last time I debriefed teaching this course, I toyed with the idea making several end-to-end passes through compilation process, inspired by a paper on 15 compilers in 15 weeks. I've been a little reluctant to mess with the traditional structure of this course, which has so much great history. While I don't want to be one of those professors who teaches a course "the way it's always been done" just for that sake, I also would like to have a strong sense that my different approach will give students a full experience. Teaching compilers only every third semester makes each course offering a scarce and thus valuable opportunity.

I suppose that there are lots of options... With a solid framework and reference implementation, we could cover the phases of the compiler in any order we like, working on each module independently and plugging them into the system as we go. But I think that there needs to be some unifying theme to the course's approach to the overall system, and I also think that students learn something valuable about the next phase in the pipeline when we build them in sequence. For instance, seeing the limitations of the scanner helps to motivate a different approach to the parser, and learning how to construct the abstract syntax tree sets students up well for type checking and conversion to an intermediate rep. I imagine that similar benefits might accrue when going backwards.

I think I'll ask Dave for some pointers and see what a backwards compiler course might look like. And I'd still like to play more with the agile idea of growing a working compiler via several short iterations. (That sounds like an excellent research project for a student.)

Oh, and the quote at the top of this entry is from Kent's addendum to his forthcoming book, Implementation Patterns. I expect that this book will be part of my ongoing process of learning, too.

Posted by Eugene Wallingford | Permalink | Categories: Computing, Software Development, Teaching and Learning

October 11, 2007 1:35 PM

Thoughts as I Begin My Taper

My taper into the Marine Corps Marathon has begun. Last week ended with a 25.5-mile long run, my longest training run in preparation for the race, for a total of 60 miles in the week, my longest week.

Time was of no concern to me on this long run. My mileage build-up has taken longer this year than the past few, coming out of a winter and spring that curtailed both my mileage and my speed. On Sunday, the weather was my friend as much as it could be, with the sun spending much of the morning moving in and out of the clouds. That kept temperatures in the upper 70s F., unlike what my brethren racing in Chicago and the Twin Cities faced.

I knew early in this run, by mile 6 or so, that I didn't "have it" this day, and that finishing would be a matter of perseverance, not triumph. I was not surprised. The gods of progress were penurious this year, so I've never quite reached the level of comfort going either long or fast that I have reached in recent years. That may well turn out to be a good thing. In past years, I ran a lot of miles going into my race and probably had worn my body out. I also probably peaked too soon, on one of the long training runs weeks before. This year, I will be undertrained rather than overtrained, and relatively rested rather than relatively spent. Veteran marathoners tell me this is good. The body can be ready.

I suppose that my taper began on Monday, but I had no reason to notice until Wednesday, when I did my first track workout of the week. Instead of ten miles, I ran eight. It was a legitimate workout -- 6x800m followed by 2.5 miles at my ambitious marathon goal pace -- but it ended two miles sooner. It's amazing what two fewer miles can do (or not do) to the body.

The primary purpose of the taper is to let the body recover from the hard work it has done in recent weeks and to consolidate the gains it has made during training. One of the training goals of the taper is focus on the quality of every run, rather than on the cross-product of quantity x quality. By running only eight miles on the track, I can concentrate on speed, whether a target speed for the intervals or the steady goal pace of my other miles. My 800m repeats are still not where they were last fall (3:11-3:13), but I did run six solid repeats at 3:16 or so, with the last two being the fastest. (Negative splits!) My Tuesday and Thursday runs this week have still been slow, but I expect that by next week my body will be ready to take every run seriously.

Earlier, I mentioned my "ambitious marathon goal pace". By this I do not mean that I have set an ambitious goal pace for myself. Rather, I mean that I have two goal paces, an ambitious one and a less ambitious one. Indeed, my ambitious goal is exactly the same goal pace I've had the last two years, 8:00 per mile. I know that I have this in me somewhere, as I have maintained that pace well for long training runs the past two years and through 19 and 21 miles of my last two marathons, respectively. Whenever I have run "marathon pace" miles in training this year, I have run 8-minute miles. And I have run as many marathon pace miles as possible, especially on the track after doing my scheduled repeats. I want to prepare my body for what it feels to run this pace while tired and maybe even sore.

My less ambitious pace is 8:30 per mile. If I were to finish my race averaging this pace, I would have every reason to feel good about my day. So I have been preparing my mind to think about both paces. One thing I will do these next couple of weeks is to decide on a race strategy. At various times this summer, I have considered planning to run the first X miles of the race at 8:30/mile, where X ranges from 5 to 16, and then deciding whether I feel strong enough to try to finish at 8:00/mile. My ultimate plan will depend some on race conditions that day, but the real question is where my confidence lies, both in my mind and in my body.

One good thing about running lots of miles at an 8:00 pace: Running an 8:30 pace feels great!

October 10, 2007 7:10 PM

Three Lists, Three Agile Ideas

Browsing through several overflowing mailboxes from various agile software development lists -- thank the mail gods for procmail -- I ran across three messages that made save them for later reflection or use in a class.

On the extreme programming mailing list, Laurent Bossavit wrote:

> How do you deal with [a change breaks lots of tests]?

See it as an opportunity. A single change breaking a lot of tests means that your design has excessive coupling, *or* that your unit tests are written at too low a level of abstraction. This is an important and valuable thing to have learned about your code and tests.

Most of the time, we treat unexpected obstacles as problems -- either problems to solve, or problems to avoid. When we operate under time pressure, we usually try to avoid such obstacles. Students often find themselves in a bind for time and so seek to avoid problems, rather using them as an opportunity to make their programs better. This is another reason to start assignments early: to have time to be opportunistic on unexpected chances to learn!

Time pressure isn't the only reason students avoid problems. Some are driven by grades, in order to impress potential employers. (Maybe this will change in a world not driven by "getting a job".) Others are simply afraid to take the risk. Our school system does a pretty good job of beating risk-taking behavior out of students by the time they reach the university, and universities often don't do enough to undo this before they graduate into professional careers.

On the agile content of Laurent's comment, he is spot-on, of course. All those broken tests are excellent feedback on a weakness in either the system or the tests. Listen to the code.

On the Crystal Clear mailing list (dedicated to discussing "the ultralight Crystal Clear software development methodology"), methodology creator Alistair Cockburn wrote:

"Deciding what to build" is my new replacement phrase for "requirements". The word "requirements" tends to imply

- that [someone can] correctly locate and pluck them,

- that they are "true"

None of those are correct. They don't already pre-exist so they can't be "plucked", [no one is] in that unique position [to locate and pluck them], and they aren't "true".

which is why I nowadays prefer to talk about "deciding what to build".

I wish that more people -- software engineers, programmers, and consumers of software and software development services alike -- would think like this! "Gathering requirements" is a metaphor that goes wrong both on 'gathering' and on 'requirements'. "Deciding what to build" creates a completely different mental image and sets up a completely different set of performance expectations. As Alistair tells it, "deciding what to build" is a negotiation, not an exam question about Platonic ideals that has a correct answer. A negotiation can take into account many factors, including benefits, costs, preferences, and time.

The developer and customer can then record the results of their negotiation in a "contract" of whatever form they prefer. If they are so inclined, the contract can take the form of a set of tests that captures what the developer will deliver, say, FIT tests. When one side needs to "break the contract", the negotiation should have specified relative preferences that enable the parties to arrive at a new understanding of the system to be built. More negotiation -- not "adding a requirement" or "not delivering a requirement".

Finally, for a touch of humor, I give you this passage from a message to the refactoring mailing list from Buddha Buck:

Our team is considering implementing the refactoring "Replace C++ With Language With Good Refactoring Tool Support". It's a major refactoring, and full implementation might take months, if we decide to do it.

There have to be some pleasant steps to execute in this refactoring, and some even more pleasant milestones. That last rm *.cpp has to feel good.

More seriously, I think there is a great opportunity to write refactorings that aren't about software architecture and code. The patterns of Christopher Alexander begat the software patterns world, which caused many of us to write the patterns of other kinds of systems, including music, management, and pedagogy. In many software circles, refactorings are behavior-preserving modifications that target the patterns of the domain. If we write patterns of management or pedagogy, then why not write refactorings that help people prepare their environments for disruptive change? An interesting question comes to mind: what does it mean for a change to a management system to "preserve behavior"? This seems like a very cool avenue for some thought, even if it hits a dead end.

October 08, 2007 8:05 PM

Go Forth and M*

It is easy to forget how diverse the ecosphere of programming languages is. Even most of the new languages we see these days look and feel like the same old thing. But not all languages look and feel the same. If you haven't read about the Forth programming language, you should. It will remind you just how different a language can be. Forth is a stack-based language that uses postfix notation and the most unusual operator set this side of APL. I've been fond of stack-based languages since spending a few months playing with the functional language Joy and writing an interpreter for it while on sabbatical many years ago. Forth is a more of a systems language than Joy, but the programming style is the same.

I recently ran across a link to creator Chuck Moore's Forth -- The Early Years, and it offered a great opportunity to reacquaint myself with the language. This paper is an early version of the paper that became the HOPL-2 paper on Forth, but it reads more like the notes of a talk -- an informal voice, plenty of sentence fragments, and short paragraphs that give the impression of stream of consciousness.

This "autobiography of Forth" is a great example of how a program evolves into a language. Forth started as a program to compute a least-squares fitting of satellite tracking data to determine orbits, and it grew into an interpreter as Moore bumped up against the limitations of the programming environment on the IBM mainframes of the day. Over time, it grew into a full-fledged language as Moore took it with him from job to job, porting it to new environments and extending it to meet the demands of new projects. He did not settle for the limitations of the tools available to him; instead, he thought "There must be a better way" -- and made it so.

As someone teaching a compilers course right now, I smiled at the many ways that Forth exemplified the kind of thinking we try to encourage in students learning to write a compiler. Moore ported Forth to Fortran and back. He implemented cross-assemblers and code generators. When speed mattered, he wrote native implementations. All the while, he kept the core of the language small, adding new features primarily as definitions of new "words" to be processed within the core language architecture.

My favorite quotes from the paper appear at the beginning and the end. To open, Moore reports that he experienced what is in many ways the Holy Grail for a programmer. As an undergraduate, he took a part-time job with the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory at MIT, and...

My first program, Ephemeris 4, eliminated my job.

To close, Moore summarizes the birth and growth of Forth as having "the making of a morality play":

Persistent young programmer struggles against indifference to discover Truth and save his suffering comrades.

This is a fine goal for any computer programmer, who should be open to the opportunity to become a language designer when the moment comes. Not everyone will create a language that lasts for 50 years, like Forth, but that's not the point.

October 06, 2007 8:16 PM

Today I Wrote a Program

Today I wrote a program, just for fun. I wrote a solution to the classic WordLadder game, which is a common nifty assignment used in the introductory Data Structures course. I had never assigned it in one of my courses and had never had any other reason to solve it. But my daughter came home yesterday with a math assignment that included a few of these problems, such as converting "heart" to "spade", and in the course of talking with her I ended up doing a few of the WordLadder problems on my own. I'm a hopeless puzzle junkie.

Some days, an almost irrational desire to write a program comes over me, and last night's fun made me think, "I wonder how I might do this in code?" So I used a few spare minutes throughout today to implement one of my ideas from last night -- a simple breadth-first search that finds all of the shortest solutions in a particular dictionary.

A few of those spare minutes came at the public library, while the same daughter was participating in a writers' workshop for youth. As I listened to their discussion of a couple of poems written by kids in the workshop in the background, I thought to myself, "I'm writing here, too." But then it occurred to me that the kids in the workshop wouldn't call what I was doing "writing". Nor would their workshop leader or most people that we call "writers". Nor would most computer scientists, not without the rest of the phrase: "writing a program".

Granted, I wasn't writing a poem. But I was exploring an idea that had come into my mind, one that drove forward. I wasn't sure what sort of program I would end up, and arrived at the answer only after having gone down a couple of expected paths and found them wanting. My stanzas, er, subprocedures, developed over time. One grew and shrank, changed name, and ultimately became much simpler and clearer than what I had in mind when I started.

I was telling a story as much as I was solving a problem. When I finished, I had a program that communicates to my daughter an idea I described only sketchily last night. The names of my variables and procedures tell the story, even without looking at too much of their detail. I was writing as a way to think, to find out what I really thought last night.

Today I wrote a program, and it was fun.

October 05, 2007 4:45 PM

Fear and Loathing in the Computer Lab

I occasionally write about how students these days don't want to program. Not only don't they want to do it for a living, they don't even want to learn how. I have seen this manifested in a virtual disappearance of non-majors from our intro courses, and I have heard it expressed by many prospective CS majors, especially students interested in our networking and system administration majors.

First of all, let me clarify something. When I say talk about students not wanting to program, one of my colleagues chafes, because he thinks I mean that this is an unchangeable condition of the universe. I don't. I think that the world could change in a way that kids grow up wanting to program again, the way some kids in my generation did. Furthermore, I think that we in computer science can and should help try to create this change. But the simple fact is that nearly all the students who come to the university these days do not want to write programs, or learn how to do so.

If you are interested in this issue, you should definitely read Mark Guzdial's blog. Actually, you should read it in any case -- it's quite good. But he has written passionately about this particular phenomenon on several occasions. I first read his ideas on this topic in last year's entry Students find programming distasteful, which described experiences with non-majors working in disciplines where computational modeling are essential to future advances.

This isn't about not liking programming as a job choice -- this isn't about avoiding facing a cubicle engaged in long, asocial hours hacking. This is about using programming as a useful tool in a non-CS course. It's unlikely that most of the students in the Physics class have even had any programming, and yet they're willing to drop a required course to avoid it.

In two recent posts [ 1 | 2 ], Mark speculates that the part of the problem involving CS majors may derive from our emphasis on software engineering principles, even early in the curriculum. One result is an impression that computer science is "serious":

We lead students to being able to create well-engineered code, not necessarily particularly interesting code.

One result of that result is that students speak of becoming a programmer as if this noble profession has its own chamber in one of the middle circles in Dante's hell.

I understand the need for treating software development seriously. We want the people who write the software we use and depend upon every day to work. We want much of it to work all the time. That sounds serious. Companies will hire our graduates, and they want the software that our graduates write to work -- all the time, or at least better than the software of their competitors. That sounds serious, too.

Mark points out that, while this requirement on our majors calls for students to master engineering practice, it does "not necessarily mesh with good science practice".

In general, code that is about great ideas is not typically neat and clean. Instead, the code for the great programs and for solving scientific problems is brilliant.

And -- here is the key -- our students want to be creative, not mundane.

Don't get me wrong here. I recently wrote on the software engineering metaphor as mythology, and now I am taking a position that could be viewed as blaming software engineering for the decline of computer science. I'm not. I do understand the realities of the world our grads will live in, and I do understand the need for serious software developers. I have supported our software engineering faculty and their curriculum proposals, including a new program in software testing. I even went to the wall for an unsuccessful curriculum proposal that created some bad political feelings with a sister institution.

I just don't want us to close the door to our students' desire to be brilliant. I don't want to close the door on what excites me about programming. And I don't want to present a face of computing that turns off students -- whether they might want to be computer scientists, or whether they will be the future scientists, economists, and humanists who use our medium to change the world in the ways of those disciplines.

Thinking cool ideas -- ideas that are cool to the thinker -- and making them happen is intellectually rewarding. Computer programming is a new medium that empowers people to realize their ideas in a way that has never been available to humankind before.

As Mark notes in his most recent article on this topic, realizing one's own designs also motivates students to want to learn, and to work to do it. We can use the power of our own discipline to motivate people to sample it, either taking what they need with them to other pastures or staying and helping us advance the discipline. But in so many ways we shoot ourselves in the foot:

Spending more time on comments, assertions, preconditions, and postconditions than on the code itself is an embarrassment to our field.

Amen, Brother Mark.

I need to do more to advance this vision. I'm moving slowly, but I'm on the track. And I'm following good leaders.

Posted by Eugene Wallingford | Permalink | Categories: Computing, Software Development, Teaching and Learning

October 04, 2007 6:40 PM

OOPSLA Evolving

I have like to write programs since I first learned Basic in high school. When I discovered OOPSLA back in 1996, I felt as if I had found a home. I had been programming in Smalltalk for nearly a decade. At the time, OOP was just reaching down into the university curriculum, and the OOPSLA Educators' Symposium introduced me to a lot of smart, interesting people who were wrestling with some of the questions we were wrestling with her.

But the conference was about more than objects. It had patterns, and agile software development, and aspect-oriented programming, and language processing, and software design more generally. It was about programs. The people at OOPSLA liked to write programs. They liked to look at programs, discuss, and explore new ways of writing them. I was hooked.

When objects were in ascendancy in industry, OOPSLA had the perfect connection to academia and industry. That was useful. But now that OOP has become so mainstream as to lose its sense of urgency, the value of having "OO" in the conference name has declined. Now, the "OO" part of the name is more misleading than helpful. In some ways, it was an accident of history that this community grew up around object-oriented programming. Its real raison d'etre is programming.

The conference cognoscenti have been bandying about the idea of changing the name of the conference for a few years now, to communicate better why someone should come to the conference. This is a risky proposition, as the OOPSLA name is a brand that has value in its own right.

You can see one small step toward the possibility of a new name in how we have been "branding" the conference this year. On the 2007 web site, instead of saying "OOPSLA" we have been saying ooPSLA. There are a couple of graphical meanings one can impose on this spelling, but it is a change that signals the possibility of more.

It has been fun hearing the discussions of a possible name change. You can see glimpses of the "OOPSLA as programming" theme, and some of the interesting ideas driving thoughts of change, in this year's conference program. General chair Richard Gabriel writes:

I used to go to OOPSLA for the objects -- back in the 1980s when there was lots to find/figure out about objects and how that approach -- oop -- related to programming in general. Nowadays objects are mainstream and I go for the programming. I love programs and programming. I laugh when people try to compare programming to something else, such as: "programming is like building a bridge" or "programming is like following a recipe to bake a soufflé." I laugh because programming is the more fundamental activity -- people should be comparing other things to it: "writing a poem is like programming an algorithm" or "painting a mural is like patching an OS while it's running." I write programs for fun the way some people play sudoku or masyu, and so I love to hear and learn about programs and programming.

Programming is the more fundamental activity... Very few people in the world realize this -- including a great many computer scientists. We need to communicate this better to everyone, lest we fail to excite the great minds of the future to help us build this body of knowledge.

OOPSLA has an Essays track that distinguishes it from other academic conferences. An OOPSLA essay enables an author to reflect ...

... upon technology, its relation to human endeavors, or its philosophical, sociological, psychological, historical, or anthropological underpinnings. An essay can be an exploration of technology, its impacts, or the circumstances of its creation; it can present a personal view of what is, explore a terrain, or lead the reader in an act of discovery; it can be a philosophical digression or a deep analysis. At its best, an essay is a clear and compelling piece of writing that enacts or reveals the process of understanding or exploring a topic important to the OOPSLA community. It shows a keen mind coming to grips with a tough or intriguing problem and leaves the reader with a feeling that the journey was worthwhile.

As 2007 Essays chair Guy Steele writes in his welcome,

Perhaps we may fairly say that while Research Papers focus on 'what' and 'how' (aided and abetted by 'who' and 'when' and 'where'), Essays take the time to contemplate 'why' (and Onward! papers perhaps brashly cry 'why not?').

This ain't your typical research paper, folks. Writers are encouraged to think big thoughts about programs and programming, and then share those thoughts with an audience that cares.

Steele refers to Onward!, and if you've never been to OOPSLA you may not be able to what he means. In many ways, Onward! is the archetypal example of how OOPSLA is about programs and all the issues related to them. A few years ago, many conference folks were frustrated that the technical track at OOPSLA made no allowance for papers that really push the bounds of our understanding, because they didn't fit neatly into the mold of conventional programming languages research. Rather than just bemoan the fact, these folks -- led by Gabriel -- created the conference-within-a-conference that is Onward!. Crista Lopes's Onward! welcome leaves no doubt that the program is the primary focus of the Onward! and, more generally, the conference:

Objects have grown up, software is everywhere, and we are now facing a consequence of this success: the perception that we know what programming is all about and that building software systems is, therefore, just a simple matter of programming ... with better or worse languages, tools, and processes. But we know better. Programming technology may have matured, programming languages, tools, and processes may have proliferated, but fundamental issues pertaining to computer Programming, Systems, Languages, and Applications are still as untamed, as new, and as exciting as they ever were.

Lopes also wrote a marvelous message on the conference mailing list last October that elaborates on these ideas. She argued that we should rename OOPSLA simply the ACM Conference on Programming. I'll quote only this portion:

Over the past couple of decades, the words "programming" and "programmer" fell out of favor, and were replaced by several other expressions such as "software engineer(ing)", "software design(er)", "software architect(ure)", "software practice", etc. A "programmer" is seen in some circles as an inferior worker to a "software engineer" or, pardon the comparison!, a "software architect". There are now endless, more fashionable terms that try to hide, or subsume, the fact that, when the rubber hits the road, this is all about developing systems whose basic elements are computer programs, and the processes and tools that surround their creation and composition.

...

While I have nothing against the new, more fashionable terms, and even understand their need and specificity, I think it's a big mistake that the CS research community follows the trend of forgetting what this is all about. The word "programming" is absolutely right on the mark!, and CS needs a research community focusing on it.

On this view, we need to rename OOPSLA not for OOPSLA's sake, but for the discipline's. Lopes's "Conference on Programming" sounds to bland to those with a marketing bent and too pedestrian for those who with academic pretension. But I'm not sure that it isn't the most accurate name.

What are the options? For many, then default is to drop the "oo" altogether, but that leaves PSLA -- which breaks whatever rule there is against creating acronyms that sound unappealing when said out loud. So I guess the ooPSLA crowd should just keep looking.

October 03, 2007 5:24 PM

Walk the Wall, Seeger

There is a great scene toward the end of one of my favorite movies, An Officer and a Gentleman. The self-centered and childlike protagonist, Zach Mayo, has been broken down by Drill Instructor Foley. He is now maturing under the Foley's tough hand. The basic training cohort is running the obstacle course for its last time. Mayo is en route to a course record, and his classmates are urging him on. But as his passes one of his classmates on the course, he suddenly stops. Casey Seeger has been struggling with wall for the movie, and it looks like she still isn't going to make it. But if she doesn't, she won't graduate. Mayo sets aside his record and stands with Seeger, cheering her and coaching her over the wall. Ultimately, she makes it over -- barely -- and the whole class gathers to cheer as Mayo and Seeger finish the run together. This is one of the triumphant scenes of the film.

I thought of this scene while running mile repeats on the track this morning. Three young women in the ROTC program were on the track, with two helping the third run sprints. The two ran alongside their friend, coaxing her and helping her continue when she clearly wanted to stop. If I recall correctly from my sister's time in ROTC, morning PT (physical training) is a big challenge for many student candidates and, as in An Officer and a Gentleman, they must meet certain fitness thresholds in order to proceed with the program -- even if they are in non-combat roles, such as nurses.

It was refreshing to see that sort of teamwork, and friendship, among students on the track.

It is great when this happens in one our classes. But when it does, it is generally an informal process that grows among students who were already friends when they came to class. It is not a part of our school culture, especially in computer science.

Some places, it is part of the culture. A professor here recently related a story from his time teaching in Taiwan. In his courses there, the students in the class identified a leader, and then they worked together to make sure that everyone in the class succeeded. This was something that students expected of themselves, not something the faculty required.

I have seen this sort of collectivism imposed from above by CS professors, particularly in project courses that require teamwork. In my experience, it rarely works well when foisted on students. The better students resent having their grade tied to a weaker student's, or a lazier one's. (Hey, it's all about the grade, right?) The weaker students resent being made someone else's burden. Maybe this is a symptom of the Rugged Individualism that defines the West, but working collectively is generally just not part of our culture.

And I understand how the students feel. When I found myself in situations like this as a student, I played along, because I did what my instructors asked me to do. And I could be helpful. But I don't think it ever felt natural to me; it was an external requirement.

Recently I found myself discussing pair programming in CS1 with a former student who now teaches for us. He is considering pairing students in the lab portion of his non-majors course. Even after a decade, he remembers (fondly, I think) working with a different student each week in my CS1 lab. But the lab constituted only a quarter of the course grade, and the lab exercises did not require long-term commitment to helping the weakest members of the class succeed. Even still, I had students express dissatisfaction at "wasting their time".

This is one of the things that I like about the agile software methods: it promotes a culture of unity and of teamwork. Pair programming is one practice that supports this culture, but so are collective ownership, continuous integration, and coding standard. Some students and programmers, including some of the best, balk at being forced into "team". Whatever the psychological, social, and political issues, and whatever my personal preferences as a programmer, there seems something attractive about a team working together to get better, both as a team and as individuals.

I wish the young women I saw this morning well. I hope they succeed, as a team and as individuals. They can make it over the wall.

Posted by Eugene Wallingford | Permalink | Categories: General, Software Development, Teaching and Learning

October 02, 2007 6:58 AM

The Right (Kind of) Stuff

As you seek the three great virtues of a programmer, you seek to cultivate...

... the kind of laziness that makes you want to minimize future effort but investing effort today, to maximize your productivity and performance over the long haul, not the kind that leads you to avoid essential work or makes you want to cut corners.

... the kind of impatience that encourages you to work harder, not the kind of impatience that steals your spirit when you hit a wall or makes you want to cut corners.

... the kind of hubris that makes you think that you can do it, to trust yourself, not the kind of hubris that makes you think you don't have to listen to the problem, your code, or other people -- or the kind that makes you want to cut corners.

October 01, 2007 7:33 PM

Easy, Unlike a Sunday Morning

... with apologies to The Commodores.

It is not often anytime, let alone during marathon training, that my Sunday long run is not focal point of my running week. This week was different.

First, it was a recovery week that called for only a 12-mile long run. That always shifts more of my attention to my in-week track sessions, which this week consisted of two 10-milers: Wednesday, consisting of 8x200m repeats followed by 5 miles at marathon goal pace, and Wednesday, consisting of 7 miles at marathon goal pace with relatively fast cool-down laps.

Second, I decided to run a 5K race on Saturday. On tired legs from the two track workouts, I had low expectations. But I figured the race vibe would be good for me, and besides I could find out how much speed I had after a week of running.

My result was unexpectedly good. I finished in 21:26, which was my 3rd fastest 5K ever and fastest since 2005, when I ran a 20:50 in June and a 20:44 in December. I even "medaled", finishing second in my age group. And I even felt good at the end -- could've run more! A good day.

Sunday's 9 miles was anticlimactic, a nice breather as I head into my stiffest week of the year: 60 miles that ends with a 25-miler next Sunday. That will be a regular Sunday.

I woke up this morning to find that Haile Gebrselassie had shaved 29 seconds off of the marathon world record on a flat course at the Berlin Marathon. 2:04:26 requires a phenomenal pace for 26.2 miles, about 4:45/mile, which is almost incomprehensible to me. I'll keep working on an 8:30/mile pace and shoot for 8-minute miles on a great day.