January 27, 2024 7:10 PM

Today in "It's not the objects; it's the messages"

Alan Kay is fond of saying that object-oriented programming is not about the objects; it's about the messages. He also looks to the biological world for models of how to think about and write computer programs.

This morning I read two things on the exercise bike that brought these ideas to mind, one from the animal kingdom and one from the human sphere.

First was a surprising little article on how an invasive ant species is making it harder for Kenyan lions to hunt zebras, with elephants playing a pivotal role in the story, too. One of the scientists behind the study said:

"We often talk about conservation in the context of species. But it's the interactions which are the glue that holds the entire system together."

It's not just the animals. It's the interactions.

Then came @jessitron reflecting on what it means to be "the best":

And then I remembered: people are people through other people. Meaning comes from between us, not within us.

It's not just the people. It's the interactions.

Both articles highlighted that we are usually better served by thinking about interactions within systems, and not simply the components of system. That way lies a more reliable approach to build robust software. Alan Kay is probably somewhere nodding his head.

The ideas in Jessitron's piece fit nicely into the software analogy, but they mean even more in the world of people that she is reflecting on. It's easy for each of us to fall into the habit of walking around the world as an I and never quite feeling whole. Wholeness comes from connection to others. I occasionally have to remind myself to step back and see my day in terms of the students and faculty I've interacted with, whom I have helped and who have helped me.

It's not (just) the people. It's the interactions.

January 21, 2024 8:28 AM

A Few Thoughts on How Criticism Affects People

The same idea popped up in three settings this week: a conversation with a colleague about student assessments, a book I am reading about women writers, and a blog post I read on the exercise bike one morning.

The blog post is by Ben Orlin at Math With Bad Drawings from a few months ago, about an occasional topic of this blog: being less wrong each day [ for example, 1 and 2 ]. This sentence hit close enough to home that I saved it for later.

We struggle to tolerate censure, even the censure of idiots. Our social instrument is strung so tight, the least disturbance leaves us resonating for days.

Perhaps this struck a chord because I'm currently reading A Room of One's Own, by Virginia Woolf. In one early chapter, Woolf considers the many reasons that few women wrote poetry, fiction, or even non-fiction before the 19th century. One is that they had so little time and energy free to do so. Another is that they didn't have space to work alone, a room of one's own. But even women who had those things had to face a third obstacle: criticism from men and women alike that women couldn't, or shouldn't, write.

Why not shrug off the criticism and soldier on? Woolf discusses just how hard that is for anyone to do. Even many of our greatest writers, including Tennyson and Keats, obsessed over every unkind word said about them or their work. Woolf concludes:

Literature is strewn with the wreckage of men who have minded beyond reason the opinions of others.

Orlin's post, titled Err, and err, and err again; but less, and less, and less, makes an analogy between the advance of scientific knowledge and an infinite series in mathematics. Any finite sum in the series is "wrong", but if we add one more term, it is less wrong than the previous sum. Every new term takes us closer to the perfect answer.

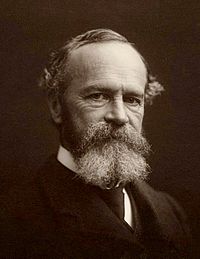

He then goes on to wonder whether the same is, or could be, true of our moral development. His inspiration is American psychologist and philosopher William James. I have mentioned James as an inspiration myself a few times in this blog, most explicitly in Pragmatism and the Scientific Spirit, where I quote him as saying that consciousness is "not a thing or a place, but a process".

Orlin connects his passage on how humans receive criticism to James's personal practice of trying to listen only to the judgment of ever more noble critics, even if we have to imagine them into being:

"All progress in the social Self," James says, "is the substitution of higher tribunals for lower."

If we hold ourselves to a higher, more noble standard, we can grow. When we reach the next plateau, we look for the next higher standard to shoot for. This is an optimistic strategy for living life: we are always imperfect, but we aspire to grow in knowledge and moral development by becoming a little less wrong each step of the way. To do so, we try to focus our attention on the opinions of those whose standard draws us higher.

Reading James almost always leaves my spirit lighter. After Orlin's post, I feel a need to read The Principles of Psychology in full.

These two threads on how people respond to criticism came together when I chatted with a colleague this week about criticism from students. Each semester, we receive student assessments of our courses, which include multiple-choice ratings as well as written comments. The numbers can be a jolt, but their effect is nothing like that of the written comments. Invariably, at least one student writes a negative response, often an unkind or ungenerous one.

I told my colleague that this is recurring theme for almost every faculty member I have known: Twenty-nine students can say "this was a good course, and I really like the professor", but when one student writes something negative... that is the only comment we can think about.

The one bitter student in your assessments is probably not the ever more noble critic that James encourages you to focus on. But, yeah. Professors, like all people, are strung pretty tight when it comes to censure.

Fortunately, talking to others about the experience seems to help. And it may also remind us to be aware of how students respond to the things we say and do.

Anyway, I recommend both the Orlin blog post and Woolf's A Room of One's Own. The former is a quick read. The latter is a bit longer but a smooth read. Woolf writes well, and once my mind got on the book's wavelength, I found myself engaged deeply in her argument.

January 06, 2024 10:41 AM

end.

My social media feed this week has included many notes and tributes on the passing of Niklaus Wirth, including his obituary from ETH Zurich, where he was a professor. Wirth was, of course, a Turing Award winner for his foundational work designing a sequence of programming languages.

Wirth's death reminded me of

END DO,

my post on the passing of John Backus, and before that

a post

on the passing of Kenneth Iverson. I have many fond memories related

to Wirth as well.

Pascal

Pascal was, I think, the fifth programming language I learned. After that, my language-learning history starts to speed up and blur. (I do think APL and Lisp came soon after.)

I learned BASIC first, as a junior in high school. This ultimately changed the trajectory of my life, as it planted the seeds for me to abandon a lifelong dream to be an architect.

Then at university, I learned Fortran in CS 1, PL/I in Data Structures (you want pointers!), and IBM 360/370 assembly language in a two-quarter sequence that also included JCL. Each of these language expanded my mind a little.

Pascal was the first language I learned "on my own". The fall of my junior year, I took my first course in algorithms. On Day 1, the professor announced that the department had decided to switch to Pascal in the intro course, so that's what we would use in this course.

"Um, prof, that's what the new CS majors are learning. We know Fortran and PL/I." He smiled, shrugged, and turned to the chalkboard. Class began.

After class, several of us headed immediately to the university library, checked out one Pascal book each, and headed back to the dorms to read. Later that week, we were all using Pascal to implement whatever classical algorithm we learned first in that course. Everything was fine.

I've always treasured that experience, even if it was little scary for a week or so. And don't worry: That professor turned out to be a good guy with whom I took several courses. He was a fellow chess player and ended up being the advisor on my senior project: a program to perform the Swiss system commonly used to run chess tournaments. I wrote that program in... Pascal. Up to that point, it was the largest and most complex program I had ever written solo. I still have the code.

The first course I taught as a tenure-track prof was my university's version of CS 1 -- using Pascal.

Fond memories all. I miss the language.

Wirth sightings in this blog

I did a quick search and found that Wirth has made an occasional appearance in this blog over the years.

• January 2006: Just a Course in Compilers

This was written at the beginning of my second offering of our compiler course, which I have taught and written about many times since. I had considered using as our textbook Wirth's Compiler Construction, a thin volume that builds a compiler for a subset of Wirth's Oberon programming language over the course of sixteen short chapters. It's a "just the facts and code" approach that appeals to me most days.

I didn't adopt the book for several reasons, not least of which that at the time Amazon showed only four copies available, starting at $274.70 each. With two decades of experience teaching the course now, I don't think I could ever really use this book with my undergrads, but it was a fun exercise for me to work through. It helped me think about compilers and my course.

Note: A PDF of Compiler Construction has been posted on the

web for many years, but every time I link to it, the link ultimately

disappears. I decided to mirror the files locally, so that the link

will last as long as this post lasts:

[

Chapters 1-8

|

Chapters 9-16

]

• September 2007: Hype, or Disseminating Results?

... in which I quote Wirth's thoughts on why Pascal spread widely in the world but Modula and Oberon didn't. The passage comes from a short historical paper he wrote called "Pascal and its Successors". It's worth a read.

• April 2012: Intermediate Representations and Life Beyond the Compiler

This post mentions how Wirth's P-code IR ultimately lived on in the MIPS compiler suite long after the compiler which first implemented P-code.

• July 2016: Oberon: GoogleMaps as Desktop UI

... which notes that the Oberon spec defines the language's desktop as "an infinitely large two-dimensional space on which windows ... can be arranged".

• November 2017: Thousand-Year Software

This is my last post mentioning Wirth before today's. It refers to the same 1999 SIGPLAN Notices article that tells the P-code story discussed in my April 2012 post.

I repeat myself. Some stories remain evergreen in my mind.

The Title of This Post

I titled my post on the passing of John Backus END DO

in homage to his intimate connection to Fortran. I wanted to do something

similar for Wirth.

Pascal has a distinguished sequence to end a program:

"end.". It seems a

fitting way to remember the life of the person who created it and who

gave the world so many programming experiences.